For the customer, the Hayward Gallery’s extraordinary new exhibition of the late work of the French-American artist Louise Bourgeois is a significant endeavor. Thanks each to its measurement – the present gathers collectively some 90 collages, sculptures and installations, lots of which have by no means been proven right here earlier than – and to the ever-confounding areas of the gallery itself, inside it takes a short while to get oriented. The eyes should alter to the Hayward’s everlasting nightfall; the physique should struggle a robust sense of expectation. You need each to hurry round in a frenzy and to commune with every little thing for minutes at a time. Ultimately, I did two circuits, one quick and one sluggish, and even then I wasn’t happy. Enfolded at midnight pleats of Bourgeois’s thoughts, the longest look nonetheless appears in some way to be cursory. Here's a sequence of caverns, every considered one of which calls for to be absolutely explored.

What’s unusual about this spirit of investigation is that Bourgeois’s follow would seem to work in opposition to it. Delicate although she might typically be, nuance is kind of unknown to her. That is artwork that’s simple to learn, the messages it semaphores near trite at moments (this can be one motive why the exhibition’s curator, Hayward director Ralph Rugoff, has saved his personal interpretations to a minimal). What else may Femme Maison (2001), through which a cloth home has been stitched to a feminine torso, be about however the burdens of ladies? What extra could be stated of Do Not Abandon Me (1999), a chunk that includes the determine of a unadorned girl and her new child child, when you’ve completed speculating to which ones – mom or little one – the worry urged by its title most applies?

And but this lack of ambiguity impedes our curiosity and pleasure not one iota. Why? I believe it has to do, typically, along with her media. Even when we’re not allowed to the touch it, taking a look at Bourgeois’s artwork is a haptic expertise: her textures are nearly as thrilling as her feeling for narrative drama (for melodrama, typically). Principally, although, it’s related to a sure lurid intimacy. As Robert Hughes stated, her work has a “queer, troglodytic high quality, like one thing pale beneath a log”. Ugh! you assume. After which: however simply let me take one other look.

The Woven Baby focuses completely on the final 20 years of the artist’s lengthy profession, an astonishing burst of late life creativity in material and textiles that was born, partially, of recollections of her childhood (she died in 2010, aged 98). We all know that her rising up was traumatic – she got here to treat her father’s affair along with her teenage governess as a type of little one abuse – however this fiery flurry isn’t solely to do with psychological ache. Bourgeois’s mother and father had been tapestry restorers, and in outdated age she returned to her roots, incorporating needles, bobbins, embroidery and weaving into her artwork.

If on a regular basis objects are right here remodeled into miniature horror reveals – in Untitled (1996), cow bones are used for coat hangers; in Untitled (2010), pale woollen berets grow to be swollen, severed breasts – what’s displayed can also be intensely home. Her totemic “progressions”, which revisit her vertical, segmented “personages” of the Nineteen Fifties, at the moment are created from supplies comparable to mattress linen and tapestry work (the latter call to mind church kneelers). Eugénie Grandet (2009), a sequence of 16 panels that makes use of the handkerchiefs and tea towels from the trousseau she introduced along with her when she moved to the US seven many years earlier than, is (to me, not less than) a form of replace of the samplers women sewed within the nineteenth century, practising their stitches. (This piece is called, in fact, for Balzac’s heroine, a personality with whom Bourgeois recognized on the grounds that her father, too, was oppressive.)

How to select issues for particular consideration in a present through which nearly every little thing is fascinating, horrifying, unusual, eerie, stunning? The primary object the attention sees is Cell VII (1998), considered one of Bourgeois’s enclosures: installations through which private objects – on this case, a scale mannequin of her childhood residence in Choisy-le-Roi, and garments that belonged each to her and her mom – could also be spied as if via a keyhole. The peeping tom impact induced by such storytelling – a sense of transgression in your half which, paradoxically, solely brings you nearer to the artist – is just not, I ought to say, uncommon.

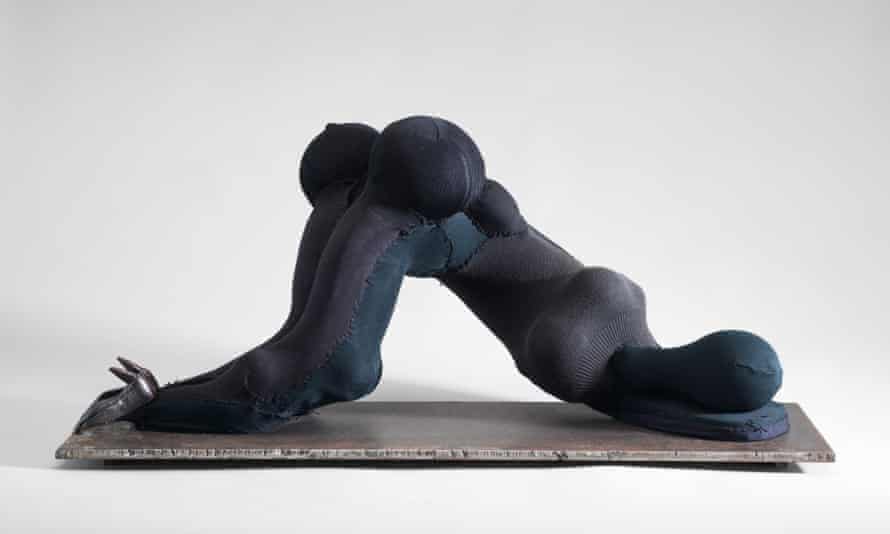

Transferring on, I nearly blushed at Excessive Heels (1998), a kneeling determine angled fastidiously to show each her buttocks and the soles of her not possible sneakers. The curator describes The Reticent Baby (2003), through which a sequence of sentimental pink figures – they signify the delivery and early lifetime of the artist’s youngest son, Alain – seem contorted within the concave mirror behind them, as a “diorama”, and in a literal sense, that is right. Actually, although, it’s a lot extra personal – and dynamic – than the phrase suggests: a flickering residence film as shot by Dr Freud.

Is there a spider? (A favorite motif of Bourgeois, arachnids, these super-weavers, stand for moms in her world.) Sure, there are a number of, the most important of which, Spider (1997), is within the upstairs gallery. This big metal monster straddles a mesh “cell”, inside that are extra of the artist’s belongings, amongst them a bottle of Bourgeois’s favorite scent, Shalimar. “The spider is a repairer,” she stated, and maybe this sense of restoration – a tapestry-covered chair can also be contained in the cage – is one motive why this piece induces a creeping sense of contentment as you circle it.

Extra probably, although, it’s merely the results of its triumphant measurement. Bourgeois was doing what she did lengthy earlier than feminism lastly made her modern; it wasn’t till the retrospective of her work on the Museum of Fashionable Artwork in New York in 1982 that she started to come back out of the shadows as an artist. However, it's inspiriting, at this level within the twenty first century, to have the ability to declare her as considered one of our personal; as a warrior who each embraces and disdains the home realm, who reads it as each haven and battlefield. The Shalimar, specifically, made me smile. These heady woody-smoky-vanilla notes floating, in my creativeness, within the air round all that metallic! In some way, this encapsulates Bourgeois for me. The feminine expertise is her dominion, and it doesn't diminish her one bit to say so. However this realm should not merely be seen. It should be sensed, deeply, from inside.

Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Baby is on the Hayward Gallery, London, till 15 Could

Post a Comment