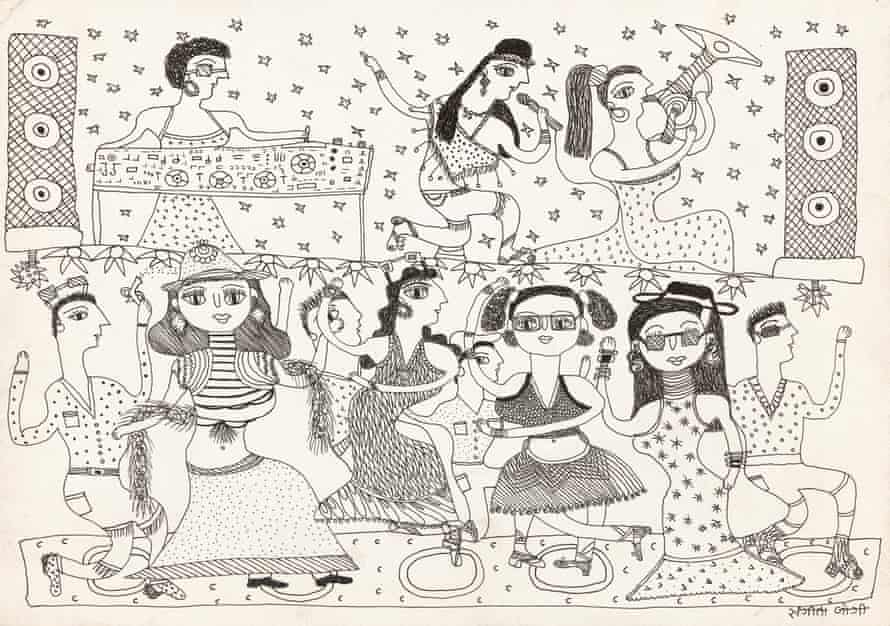

Sangita Jogi’s illustration Girls Partying, a joyful depiction of an all-girl disco nightclub, appears very very similar to one thing you would possibly see in Teen Vogue. In actuality, it’s on the wall on the Nationwide Gallery of Victoria, as a part of a brand new exhibition highlighting new acquisitions from up to date Indian artists in rural, regional, and Indigenous traditions, some handed down for hundreds of years. What is exclusive about 19-year-old Sangita is that she works in a method practised solely in her household: Jogi artwork, an lively drawing type utilizing in black ink on white paper, that includes detailed patterns and huge, advanced composition. It’s been practised for 3 generations of the Jogi household – which is to say, it’s startlingly trendy.

“What’s distinctive about this household, versus others, is that they haven’t inherited this type,” says Wayne Crothers, senior curator of Asian artwork on the NGV. “It’s come out of them preserving their narrative traditions or their singing and performing traditions.”

“I used to be impressed by the thought of ladies celebrating,” Sangita says of her work. “Girls are so burdened, and girls who're poor, much more so. So I simply considered making a piece concerning the reverse state of affairs – of ladies having fun with themselves”.

The Jogi artform began with Sangita’s mother and father, Ganesh and Teju. Their household identify derives from their group, the Jogi, in rural Rajasthan. Untrained in visible artwork, the Jogi have been historically roving musicians, singers of devotional songs and tales. Their music additionally had a sensible operate.

“The Jogi have been the alarm clocks of earlier instances,” says Minhazz Majumdar, a New Delhi curator who labored with the NGV on the exhibition. “They’d sing songs on the morning time … we all the time had a barter system going, someone would pay them.”

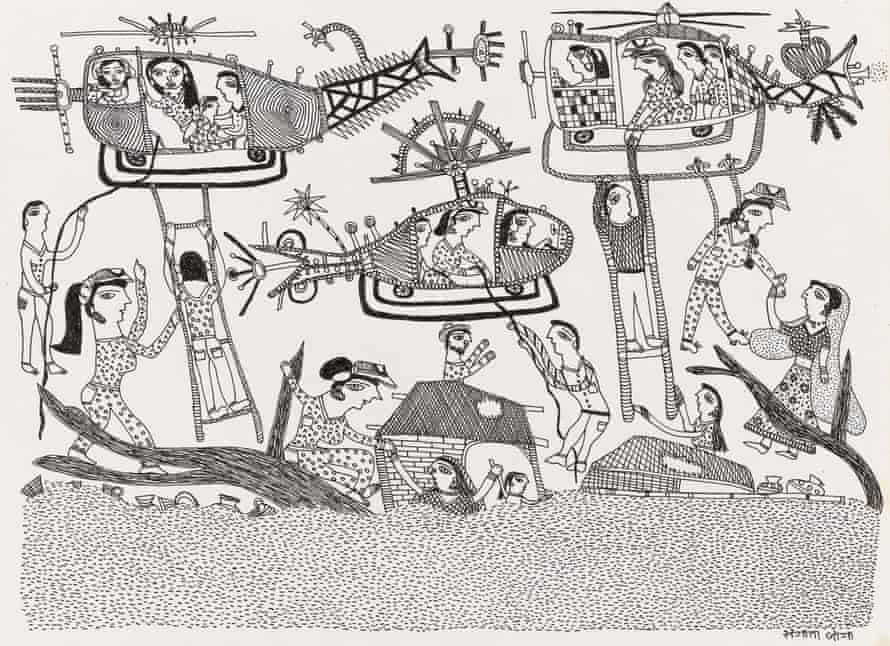

By the Nineteen Seventies, urbanisation was making such a livelihood more and more untenable. Then extreme drought hit. Going through crop failure and famine, Teju and Ganesh have been compelled to maneuver to town of Ahmedabad, Gujarat, looking for work – usually harmful, low-paid guide labour.

It was then that Ganesh met anthropologist Haku Shah, a part of a wave of Indian students and curators searching for to protect cultural traditions threatened by the tempo of social change. Shah urged Ganesh to file the narratives in Jogi songs, to guard them from being misplaced to historical past. Ganesh couldn't write, so Shah urged he draw the tales.

“He was so scared he would break the pen at first,” says Majumdar – she’s labored with the household for over 20 years – “and now, the kids do it in their very own type.”

Ganesh and Teju had 10 youngsters, of whom six have survived; all of them paint and draw.

“Drawing is sort of a meditation, like a therapeutic area for me – I lose myself in my drawings, in creating all the small print … they make me overlook my struggles,” says Prakash, Sangita’s older brother.

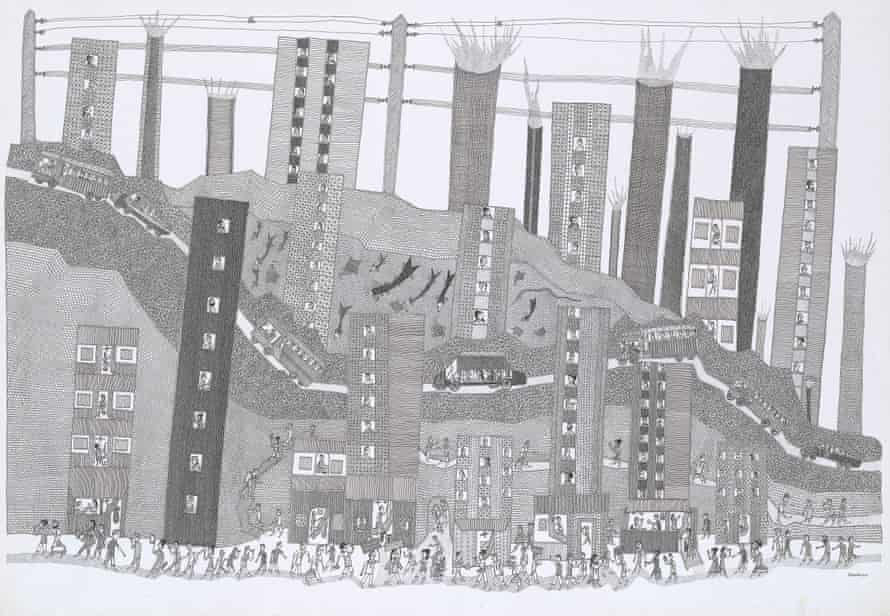

In his intricate work Cityscape (2017), Prakash depicts his dwelling in Ahmedabad the way in which he noticed it as a baby; tall house blocks, puffing smoke towers, and lots more and plenty of tiny human figures scurrying between them, uniformly intent on their enterprise, ignoring the fish and turtles within the Sabarmati River that winds via town. A detailed look reveals each determine is exclusive – all of them have totally different socks, or hair, or eyes.

Prakash is educating his teenage son to attract within the Jogi type; no one within the household sings any extra, besides Teju and Ganesh. However whereas the Jogi household’s pivot to an entire new medium is dramatic, all of the artwork varieties featured within the exhibition are present process speedy transformation.

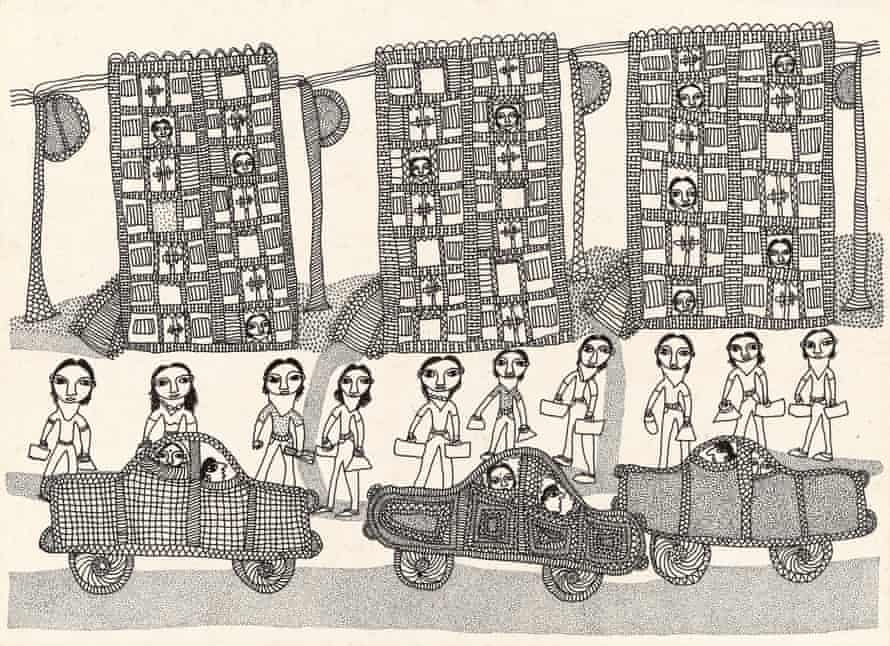

“A number of these households, who've been practising these works for hundreds of years and centuries, it’s been extra inside the home context,” says Sunita Lewis, challenge officer on the NGV. “However the previous few a long time, they’ve been altering the medium, or they’ve been altering the themes, with a view to make them a commodity and attain a far wider viewers than simply their very own communities.”

“Commodity” is a phrase curators usually draw back from, however these artists aren’t hobbyists or members of India’s city center class. Artwork is their livelihood: if their traditions are to outlive and keep related, they want a market. Sujuni, a method of embroidered quilt, was historically a method for girls to reuse scrap material for sensible items; now, they’re made for show to promote on the worldwide artwork market, offering village girls with a livelihood. Up to date sujuni work usually options motifs of ladies’s independence like laptops and mopeds. Equally, Madhubani artwork originated with murals painted in properties for important occasions like marriage and childbirth; now, Madhubani artists are engaged on paper with a view to promote or show their artwork internationally, tackling themes like local weather change, feminine foeticide, and Covid-19.

Artists are additionally more and more signing their work – one thing that wasn’t all the time finished prior to now, or demanded by collectors. A lot of the older works within the NGV exhibition are by unknown or unrecorded artists.

“The truth that the market has woken up is making it simpler now to advertise these artists as artists, and never as anonymous, faceless carriers of custom,” Majumdar says.

However, she concedes, elevated curiosity from the artwork market doesn’t all the time translate right into a safe future for artists. For probably the most half, the Jogi household are nonetheless just about the place they have been 20 years in the past – besides Sangita, who just lately moved away from Ahmedabad. She lives in rural Rajasthan along with her husband, and he or she’s simply had her first little one – a lady.

Sangita has by no means been dancing in a nightclub. Girls Partying, she says, was based mostly on events she’s seen in motion pictures and TV, and her creativeness.

“My type is extra fantasy-like, in comparison with my household,” Sangita says. “I draw what I want to see – empowered girls having fun with life.”

And, she says, she’s educating her daughter to attract.

Altering Worlds: Change and Custom in Up to date India, at NGV, free admission, till 28 August.

Minhazz Majumdar supplied translation work on this characteristic.

Post a Comment