I first met Dayanita Singh in India in 2011. Her home was an hour’s drive from a spot I used to lease in Goa each January and February to write down. As we stood in her half-lit studio taking a look at black and white images of what she referred to as “archive work”, we may hear the hum of the small gathering Singh had organised: a cocktail party that had spilled out on to the terrace and included the writers Kiran Desai and Amitav Ghosh. Earlier, the dialog had touched upon a crocodile that had been seen roaming round a swamp close to the home. Outdoors, the night time was darkish and navy blue. Inside, as I studied these images within the gloom, some very previous and really acquainted reminiscences started to floor in my thoughts. However no, the phrase “reminiscences” doesn't suffice. What was coming to life inside me was an emotion stirred by these reminiscences – and it appeared as if these images had been taken exactly to seize it.

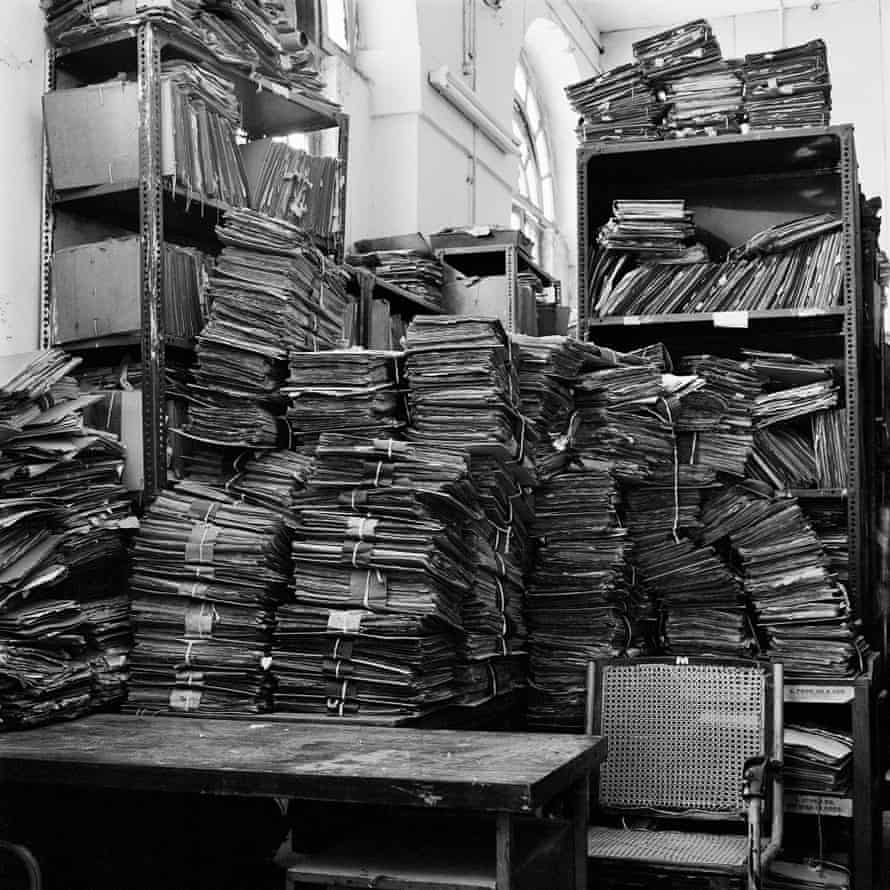

What has most drawn me to Singh’s work are the pictures collected in her books File Roomand Museum of Likelihood. In these, we discover black and white pictures of India’s huge state archives, storerooms and registry workplaces. As we leaf by these books, we turn out to be stuffed with an concept of poetic decrepitude and a way of profundity: as soon as upon a time, individuals slogged and toiled; they submitted numerous requests; they despatched petitions and filed lawsuits; they wrote about and categorized one another’s actions; and, on the state’s encouragement and behest, they saved an uninterrupted report of all of it.

Ultimately, all this vigorous exercise got here to an finish, and what was left behind had been these paperwork, these recordsdata, these baggage, and the steel cabinets and cupboards that maintain and protect all of them. Singh’s black and white pictures of these stacks of lead-grey folders, of steel, of previous and pale papers – all of which appear to be coated in mud even after they weren't – make me conscious of what I'd name “the feel of reminiscence”.

Whether or not we protect previous objects, stones and crockery, or fee full-colour work to hold up someplace within the perception they're everlasting, whether or not we painstakingly acquire each scrap of paper now we have ever written something on (I'm a type of individuals) or belief naively within the infinite capability of images and digital storage, the preservation of the previous is, in reality, an not possible endeavour. Reminiscence by no means leaves us a lot to carry on to.

However maybe it's not the main points inside reminiscences that attraction to us, a lot as their aura – of being one way or the other bottled inside objects that populate our current. Inevitably, the aura will elicit in us a form of melancholy, simply as once we have a look at historic Greek and Roman ruins and at deserted monuments. The explanation we discover these soiled, dusty, colourless recordsdata to be so “lovely” is that, due to Singh’s skilful digicam, they reveal the accrued melancholy inside us.

When this temper is captured in the identical body because the faces and shadows of among the clerks who labored in these previous storerooms, cellars and archives, we start to sense that the sensation of melancholy these archives evoke in us is, the truth is, carefully related to a sure lifestyle. In addition to that specific emotion that I've been searching for to establish, Singh’s images additionally convey a way of humility within the face of life, of stepping again, of dignified resistance even when the passage of time makes all the pieces meaningless.

Take the picture of the clerk surrounded by recordsdata and folders from File Room. The girl – who spends her life amongst heaps of yellowing paperwork, bundles of folders tied along with string and cabinets heaving with papers – is sporting an optimistic smile that provides the sensation that there's something each logical and vital in her Kafkaesque exertions.

However alongside this poetic and allegorical sensibility, I additionally see a realist aspect in Singh’s images. These, like me, who're mesmerised by her pictures will discover that they will scent the actual scent of these towering piles of historic, yellowing papers stacked in archive rooms and in and on high of steel submitting cupboards. In his essay on previous, decaying archives and the images of Singh, the author Aveek Sen reminds us that the principle supply of that singular scent that pervades India’s state archives is the rice paste used within the manufacturing of paper.

Invisible creatures referred to as home mud mites wish to gobble this rice paste up, leaving holes of their wake, and finally filling archive rooms with clouds of mud fabricated from minuscule paper particles. The cooling breeze of a ceiling fan (that quintessential emblem of the federal government workplace that we will normally spot someplace close to the highest of Singh’s photographs of archive rooms) and even the drive of an individual’s cough (for it's not possible to not cough in an archive) are sufficient to disintegrate what's left of those previous papers, lengthy since turned to mud by the ravages of those mites and time.

Indian archives – locations able to turning even the healthiest individual into an asthmatic – additionally purchase their attribute scent from the flooding that follows monsoons. Waterlogged folders, when left to their destiny, will begin spreading a peculiar scent of mushrooms and damp. If the recordsdata are taken out one after the other (a near-impossible process) and put out to dry within the solar, a scent we would describe as river muck and fish slime will quickly materialise.

I'm drawn to those particulars due to the related scents I'd scent as a toddler. I noticed the identical cupboards, monumental folders and mountains of recordsdata within the Turkish authorities workplaces I visited within the Sixties with my mom and brother every time we needed to acquire vaccine data or property deeds or register a delivery. Whilst a toddler, I may really feel that the spell of that huge and monstrous entity we referred to as “the state” exerted a far deeper pull in these locations than it did at college, in army ceremonies, or throughout Republic Day celebrations.

What primarily made the state a state weren't its troopers and police, however these folders, data, paperwork and papers. Generally our lives would fail to align as we had been instructed they need to with all of the papers mouldering in these ageing buildings, when there was an error or a spot in my vaccine data or, as would occur later, in my file on the conscription workplace. This could immediate the police or the military to come back and punish me. In different phrases, the true supply of the state’s energy weren't troopers and policemen, however these official data that had accrued over a whole bunch of years.

The strict, imperious tone that a lot of the clerks in these authorities workplaces took with us – in addition to the truth that nothing ever went easily (there at all times gave the impression to be a mistake or one thing lacking) – all heightened our notion that the state was highly effective and we had been weak. Though these data, these lots of paperwork, had been destined to show into mud inside 60 or 70 years, they had been nonetheless stronger than we had been. Maybe that's the reason Singh’s images felt like reminiscences to me.

The aura contained in what Singh calls archive work seeps into her different photographs, too. We see this most clearly in Museum Bhavan, a sequence of little booklets organized in a field. Like me, Singh likes issues which can be framed, objects seen by panes of glass. Once I leaf by the 26 pictures of museums, vitrines, show cupboards and framed objects collected in one of many booklets, The Museum of Vitrines, it appears clear there's something museum-like in Singh’s world. That smooth mild that comes from registries and archive rooms, in addition to a specific type and method of framing, are additionally coherent with the Little Girls Museum, a sequence of portraits Singh took within the houses of Indian households.

It's as if the way in which to completely take up India’s infinite crowds, its endless visitors jams and commotion, its mighty sunshine and its distinctive historical past, is to withdraw to locations whose ambiance is the very reverse, to areas protected by frosted glass, by tulles and curtains, by closed or half-open home windows, by night time, fog and shadows. In these areas – as within the previous archive rooms that embody the historical past and the politics of a nation and the feel of its reminiscence – we might not be capable of see the precise cacophony of the world outdoors, its chaos and its quarrels. However what we do discover, bathed in unusual mild, are individuals and objects which can be indifferent from that world whereas reminding us of it.

The objects captured in these pictures appear to exude a form of silence. However, in the end, what reminds us of the entire of India, in addition to the entire of the previous and the halo and aura of archive rooms, is that particular mild Singh’s digicam deftly captures. It's the unmistakable signature of this nice photographer.

Written for the Hasselblad Basis together with the Hasselblad award 2022 and the e-book Dayanita Singh: Sea of Recordsdata. Translated from Turkish by Ekin Oklap.

Post a Comment