‘I was born with zero expertise,” says Christopher Wool, ponytailed, flannel-shirted and 67. He smiles sweetly. “So I needed to work at it.” We’re in Brussels, on the Xavier Hufkens gallery the place the post-conceptual, postmodern, post-neo-expressionist summary artist imbued with a punk sensibility is having a second. Wool’s first huge European survey is drawn principally from a current artistic flowering within the Texas desert. “I used to be liberated by the pandemic. I may make artwork 12 hours a day,” he says.

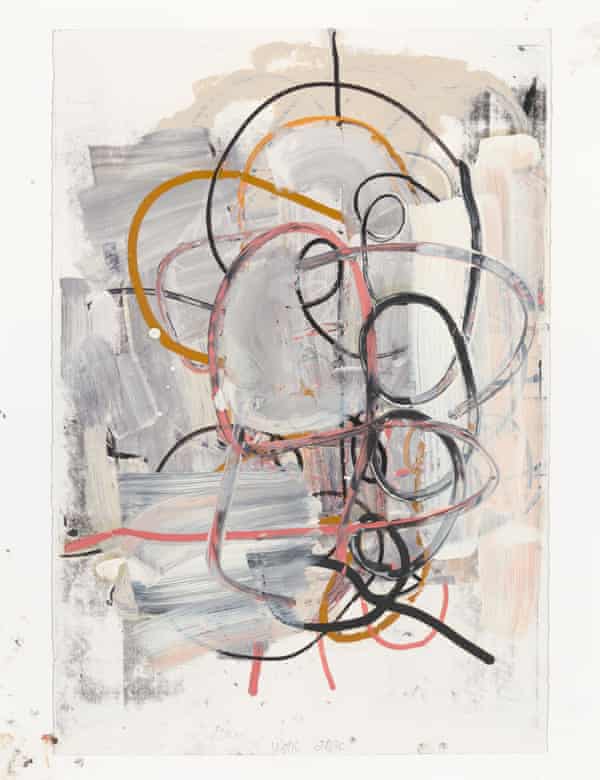

The present is a gloriously austere affair, that includes bits of twisted barbed wire, pictures of abject waste and 4 grand work made in his New York studio that originally seem like redacted textual content. Thick layers of oil paint obscure earlier layers of labor in these work as if, overwhelmed by nervousness and doubt, Wool sought to deface them.

Earlier this week, a customer to the Louvre in Paris smeared cake on the Mona Lisa. Wool wants no such assist: he auto-destructs his works, overpainting them to the purpose of obliteration. He mentions a phrase he and his spouse, the painter Charline von Heyl, get pleasure from saying: “Whenever you go away the studio and assume you’ve had day, you in all probability haven’t.” He explains: “For me, it was by no means about making masterpieces. That’s what postmodernism means to me, the tip of that modernist concept that the artist makes good works. I make a whole lot of errors however I hold them. I exploit them and recycle them.”

Like a hip-hop musician, he samples outdated materials, however with one twist. The supply materials is more and more his personal – remaking outdated work and photographs, defacing, deconstructing, or just mucking about. “I don’t make masterpieces however I make artworks that may be robust in one other means. It’s just like the distinction between the Beatles and the Intercourse Pistols. Or possibly that’s not comparability.”

Within the Xavier Hufkens gallery, there are plinths displaying bits of barbed wire that Wool discovered whereas residing in Marfa, the artists’ colony within the west Texas desert made well-known by the TV adaptation of Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick, which starred Kevin Bacon and Kathryn Hahn. Some he twisted into new shapes. One he blew up, with the assistance of an obliging foundry, right into a 3-metre monumental bronze that dangles menacingly from the ceiling.

However some bits of discarded wire are merely introduced as discovered objects, as if one thing chucked into the wilderness by a ranch hand was as aesthetically vital as something moulded by the artist’s hand. Anne Pontégnie, Wool’s curator, believes there’s a way of self-deprecation constructed into his work. She is correct – together with nervousness, self-erasure, self-sampling and a cheery disregard for making full masterpieces. Actually, his works are by no means completed: they continue to be open texts that he can, ought to he select, deface much more.

What should not on present, although, are the acerbic textual content work which have made Wool wealthy and well-known. His contemporaries Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer created textual content works satirising consumerism. Kruger: “I store due to this fact I'm.” Holzer: “Shield me from what I would like.” However Wool’s work was extra terse and enigmatic. Organized throughout three decks, one learn: “TROJNHORS.” One other – unfold throughout 5 decks, breaking apart phrases and echoing a line from Apocalypse Now declared: “SELL THE HOUSE SELL THE CAR SELL THE KIDS.”

Better of all, one work featured “FO” on one line and “OL” beneath. It was referred to as Untitled (Idiot) (1990). In keeping with one critic, the piece was in a position to “concurrently confront and satirise the viewer’s seek for which means”. Idiot offered at Christie’s in 2014 for $14m to a non-public bidder who, presumably, is satirised day by day by the acquisition. A yr later, the equally configured Untitled (Riot) (1990) went for a staggering $29.9m.

Wool makes these auctions sound like violations: “It doesn’t simply really feel such as you’re in a automotive you’re not driving,” he as soon as mentioned. “It feels such as you’re tied up within the again and nobody is even telling you the place you’re going.” After I quote these phrases at him, he says: “I don’t bear in mind saying that, but it surely sounds about proper.” When he talks to me about these gross sales, he focuses not on the hundreds of thousands he pocketed, however on his annoyance that the sale of Riot meant it couldn't be exhibited in a present he had on the Guggenheim. “Cash is just not what he's about,” says Pontégnie, who has labored with Wool for 20 years. “He's in love with portray.”

Wool was raised in Nineteen Sixties Chicago. “It was a wonderful place to be,” he says. His mom was a psychiatrist, his father a molecular biologist. “They had been that I noticed stuff after I was younger.” Aged 11, he attended a present by The Furry Who artwork collective. Later, he noticed Roscoe Mitchell, frontman of iconoclastic Afrofuturist jazz combo the Artwork Ensemble of Chicago. Each gave him a way of artwork’s subversive energy.

By 1972, he was in New York. “I used to be younger and able to insurgent in opposition to something. The chances appeared infinite. Everybody was artistic, even when the creativity didn’t lengthen to greater than, say, three chords. There was a DIY aesthetic that actually spoke to me.” He didn’t initially need to paint. “I needed to be a film-maker. However I realised I’m not a collaborative particular person.” With that typical self-deprecation, he provides: “Portray was the least adventurous factor to do. So I turned a painter.”

In the future, he had an epiphany whereas watching his landlord paint the halls of his condominium constructing utilizing a curler that left a floral sample. The glitches and misses resonated deeply with Wool. He favored how a curler or silkscreen would depart poignant traces and imperfections. He as soon as spent hours with a photocopier feeding a picture after which its copy by way of many times, overlaying it with increasingly lurid colors. “I’m within the accidents of copy,” he says.

Whereas others within the Photos Era, comparable to Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince, had been plundering adverts for uncooked materials, Wool breathed new life into portray along with his poetry of errors and mishaps. He cleaved in the direction of summary portray rendered by way of synthetic means, increase layers to create aesthetic distance. The critic Walter Benjamin feared that the age of mechanical copy – pictures, information, movies – would destroy the art work’s aura. Wool appears to subvert this, utilizing simply such mechanical methods to convey the aura again to artwork, one thing lengthy thought to have been lifeless and buried.

He makes use of images loads, documenting phases of his work in addition to creating materials to pattern, however he additionally enjoys capturing his nocturnal rambles within the footsteps of corpse-chasing photographer Weegee by way of the imply streets of New York. East Broadway Breakdown, a guide of photographs taken within the Nineteen Nineties, is like Weegee with out the lifeless our bodies.

Scenes of depersonalised abjection – city trash, views of nothing very a lot – echo Martha Rosler’s earlier conceptual Bowery pictures, the place the road drinkers had been off digital camera however their discarded bottles had been centre stage. Wool holds up his palms and arranges his fingers to simulate an oblong photographic body. “All people takes an image of that,” he says. Then he lowers his palms somewhat. “I take an image of that.” His eye goes the place others disdain to look.

On the Brussels present, Wool’s pictures of the Texas desert echo these photographs he took of New York within the 90s. Utilizing a low digital camera angle, he depicts not the desert’s grandeur, however its draw back: rutted empty roads, a discarded mattress body, towers of tyres. What comes throughout is aridity, loneliness and vacancy.

Texas was nothing in need of inspirational. “The openness of the panorama,” he says, “felt prefer it was meant for sculpture.” Certainly, being in Marfa modified how he labored. “I began to sculpt however, being new to sculpture, I don’t know the right way to do it.” There’s that self-deprecation once more, that sense of getting zero expertise and having to beat it. Wool smiles and provides: “I work at it.”

Post a Comment