“When you pick up Yael today, the principal needs to see you.” It was a one-line email from my first grader’s teacher, but it was enough to twist my stomach in a knot.

It was her first year at the school, and I had yet to meet the principal in person. So, when I showed up to her office, my daughter’s hand in mine, I had a wide smile plastered on my face, and eagerly extended my hand. She shook it limply.

“We have a problem,” she said. This happened 10 years ago, and I can still see her face.

After setting up Yael with a book outside the office, I sat down, my heart racing. It was decades since I had been called to the principal’s office, but I could still feel a shiver of anxiety.

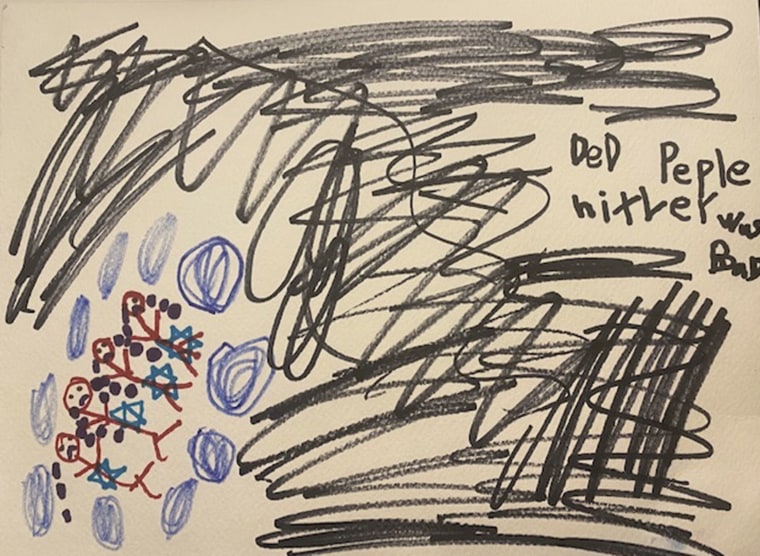

“Your daughter drew a picture of dead people today.” She picked up the piece of paper by the corner as if it was a dirty rag. My daughter had drawn stick figures jumbled in a heap, something resembling black tears streaming from their faces.

The principal seemed to be waiting for an expression of shock or dismay. I paused before blurting: “Well, today is Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day. We have been talking about this at home.”

She stared at me, her mouth pursed, still holding the paper as if she was presenting a murder weapon to a jury.

“My grandfather was a Holocaust survivor,” I stammered. “We lost a lot of our family in the Holocaust. It’s a big part of my family’s history.”

“Well, your daughter is 6 years old.”

“Yes, I know.” I was feeling my nervousness tip toward anger.

“This is not acceptable for a 6-year-old to know about.”

I took a long breath and let it out between clenched teeth. “And why is that?”

She gave the drawing a little shake, as if nothing could be more obvious.

“Yes,” I said, more firmly. “People died in the Holocaust, just like that.”

As a mental health professional, and as a parent, I am keenly aware of the need to teach children in an age-appropriate manner. But as a direct descendent of Holocaust survivors who are rapidly disappearing, I am equally mindful of the need to keep their memory alive.

Since this incident happened with my daughter a decade ago, erasure of the Holocaust in popular culture has only worsened. A 2020 survey of Americans found that 63% did not know that 6 million died in the Holocaust; over half of those thought the toll was under 2 million. And it doesn’t stop there. Book bans like those infamously propagated by the Nazis have reached unprecedented levels. In 2022, PEN America reported that there were 2,532 instances of individual books being banned, including “Night” by Elie Wiesel, “The Diary Of A Young Girl” by Anne Frank, and “Maus” by Art Spiegelman.

Walking home that afternoon, Yael asked me: “Did I do something wrong?”

“No honey, you didn’t. Some things are just hard to talk about, even for grown-ups.” Despite my reassurances, I was wondering the same thing. Had I done something wrong?

We are all familiar with those haunting images of children being herded in long lines to the Nazi gas chambers, unaware of the fate that awaited them. It’s a powerful metaphor. Just because they may not have a frame of reference with which to understand the scale of tragedy in the world does not mean that our kids don’t feel the same feelings of helplessness that we do. The antidote to powerlessness is empowerment, but how do we empower our children if we keep them in the dark?

How do we empower our children if we keep them in the dark?

If my daughter’s principal had asked, I would have explained to her the careful, kid-sensitive scaffolding I built around the historical event that more than any other defines her identity — how I told her that there was a war, in which many people died because of their religion, sexual identity or physical disability; how I read her children’s books that get across the facts in an age-appropriate way, although we did skip a few pages here and there. Books like “The Cat with the Yellow Star” or “Love the World,” which is about a dear family friend, Bronia Roslawowski, who was born in Poland, survived a concentration camp and devoted the better part of her life to teaching the Holocaust to children just like Yael. She also, more than anyone else, taught me that learning about the Holocaust and learning to value life are not only compatible, they are inextricably intertwined.

" height="2500" width="1790"/>

" height="2500" width="1790"/>

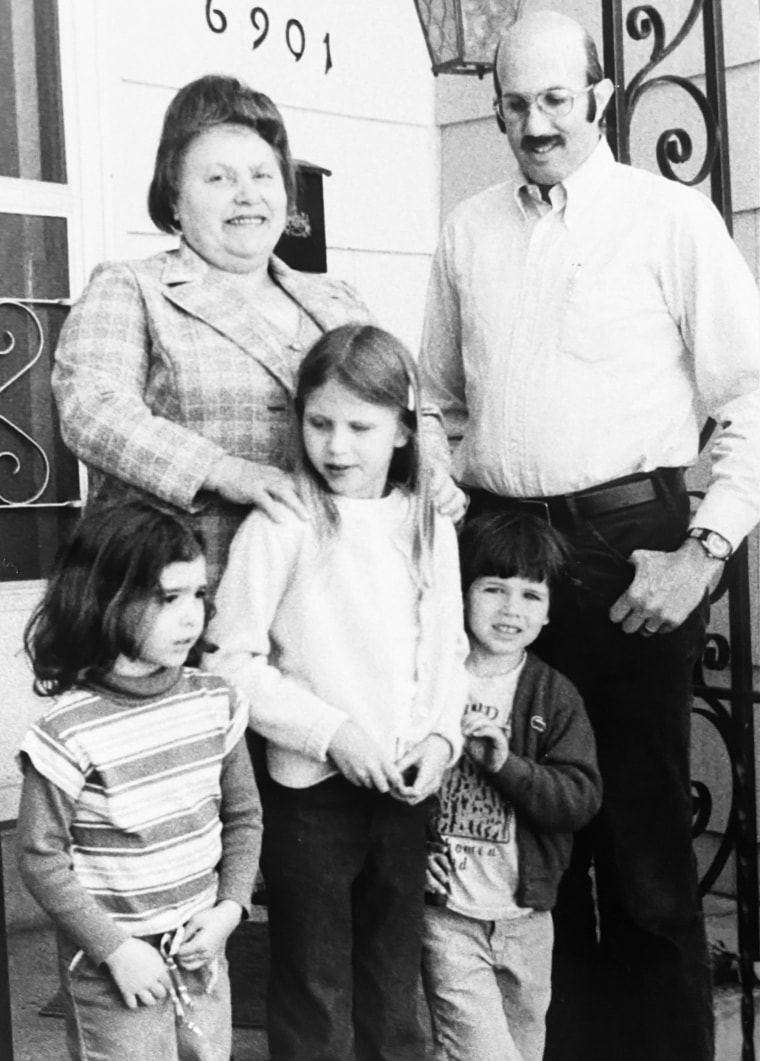

Courtesy Sarah Gundle

I would also have explained that Yael and I talked about hope — about Jews who resisted the Nazis, and about non-Jews who risked their lives to save thousands of us, including members of our own family. Also, how we talked about why people yearn to live, and how important it is to hug each other every day. Finally, I would have recounted how we discuss the work I have done over the last 25 years with those seeking asylum, and how I wish I could have told my beloved grandfather about it because he sought refuge in America and loved this country fiercely for having granted it.

But she didn’t ask. She, at least back then, seemed to believe that the Holocaust is something children are not ready to know about. It’s clear that many people still believe that today. I disagree. I believe that we must expose children to the trauma of history, and that it’s possible to do so in language and concepts they can understand. When we wait to teach a dark part of history until they are “old enough” to fully metabolize the story, they are also old enough to keep it at a distance, to justify or explain away its horror.

Delaying exposure to what happened is not being respectful of the child; it’s tragically disrespectful of the victims, part of the process of forgetting. If “Never Again” is to not become a meaningless platitude, we must give our children — yes, even our 6-year olds — the opportunity their ancestors never had of knowing the truth.

Post a Comment