At 8 years old, I was the youngest member of my Weight Watchers group by more than a decade. My weight has been a struggle my entire life — I honestly don’t remember a time, even as a child, when it wasn’t an issue.

Over my 44 years, I’ve had some weight-loss successes and even more setbacks, trying the latest fads and trends including medication, group counseling, “fat camp,” personal training, counting calories and counting carbs. I gave up grains, dairy and sugar. I even tried Nutrisystem for about a day (I wasn’t a fan).

I tried everything except for one important thing. But I’ll get to that later.

In addition to being a plus-sized person, I am also a writer. And since writers are often told to “write what you know,” it probably comes as no surprise that I have never, not once, written a skinny character.

But it might surprise you to learn that in the 10 novels I have written or co-written (only four are currently published), I’ve never written a plus-sized character. I usually avoid describing a character’s body size at all, letting readers’ imagination fill in the blanks. Until now.

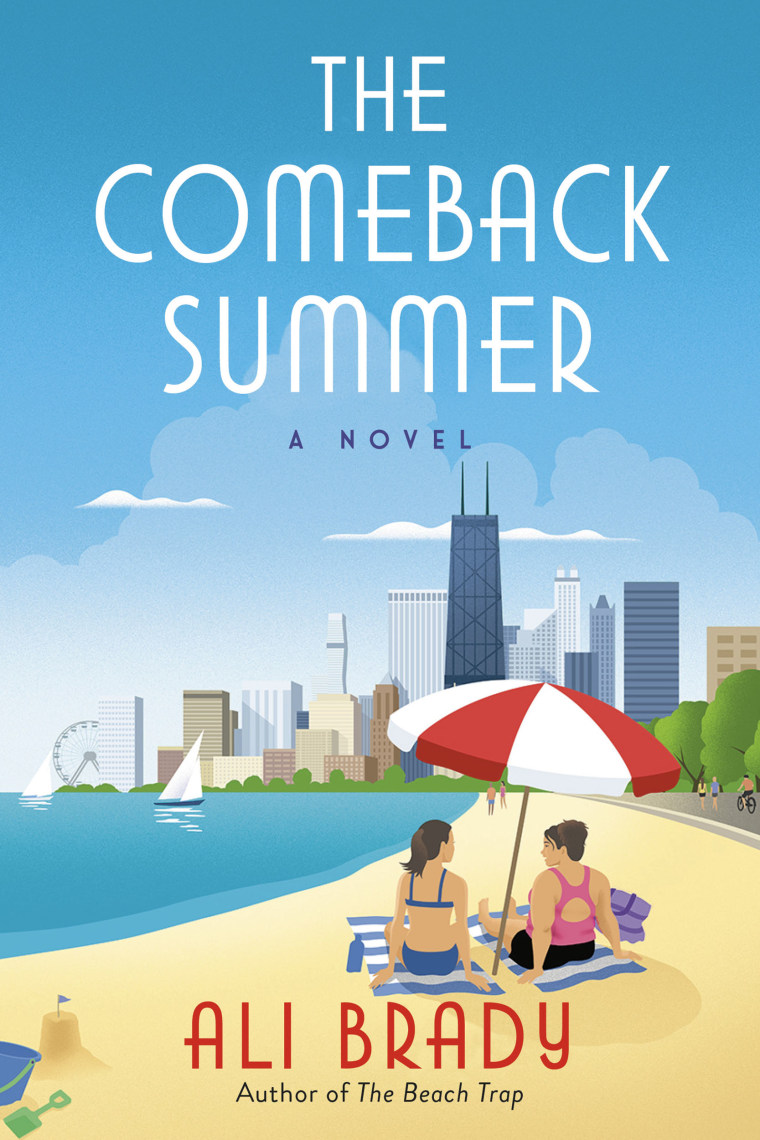

Libby Freedman is one of the leading ladies in “The Comeback Summer,” the most recent novel I co-wrote with my BFF, Bradeigh Godfrey, under the pen name Ali Brady. Libby is smart and funny and loyal to a fault. She loves romance novels, her cranky cat and her little sister, Hannah, more than anything in the world. She’s also a plus-sized woman.

I was excited and a little apprehensive about writing Libby. Talk about writing what you know: the feelings of insecurity, the sting of rejection and the desperate desire to fit into a world that puts so much value on physical beauty — a beauty that tends to be defined in a way that doesn’t include you.

But it’s one thing to live those experiences and quite another to write about them. To dig deep and put words to so many wounds that have been pushed down and brushed aside for decades. Like how it felt in junior high to go shopping with friends at stores that didn’t carry your size (thank goodness for the accessory section, so I could at least buy something!). The sinking feeling when you’re looking for an empty seat on a city bus, and everyone is avoiding your eyes, hoping you don’t sit next to them. The anxiety of showing up for a first date and hoping you look enough like your pictures that your date won’t say something hurtful or cruel.

As challenging as it was to revisit those memories, it was just as difficult to keep my personal insecurities from overtaking the character of Libby. Because as much as we have in common, I am not Libby and Libby is not me. She’s better than I am — braver and stronger and wiser in so many ways.

Throughout the writing process, Bradeigh and I had many conversations around the idea of body image. We wanted Libby’s experience to be authentic, but not triggering. We wanted her struggles with weight to be a part of who she is, but not her whole identity.

One particular scene stands out, when Libby and Hannah are training for a big race they signed up for together. Having been allergic to exercise for most of her life, Libby is struggling, but making progress.

After reading my first draft of the chapter, Bradeigh suggested that Libby take a moment to think about her body with love. My immediate reaction was no way, absolutely not. I couldn’t wrap my head around that feeling. It felt too soon — Libby hadn’t made enough progress to start loving her body. She wasn’t there yet.

But then I realized I was the one who wasn’t there yet. Not Libby. That’s when I discovered that one of the hardest parts of writing a character who shares some of your struggles is allowing that character to experience growth that you haven’t achieved. It forced me to look in the metaphorical mirror and accept that my inner self needs just as much love and kindness as my outer self.

Change like that can’t be rushed, but I knew that I needed to try and let go of those unhealthy feelings so they didn’t impact Libby. Instead, I tried to let Libby’s thoughts and actions influence me.

In the end, we didn’t go as far as having Libby outright express love for her body in that scene, but she does take a moment to appreciate it. That’s another thing Bradeigh and I have talked a lot about: the unrealistic and potentially harmful side of the body positivity movement. The suggestion that we must love our bodies, always. But that’s not possible. We all have days when we don’t feel our best, or things about ourselves we wish we could change — and that’s OK. In fact, it’s normal. And while it can feel empowering to say that every body is beautiful, those words still keep the emphasis on beauty as a measure of our value.

(We) have talked a lot about the unrealistic and potentially harmful side of the body positivity movement — the suggestion that we must love our bodies, always. But that’s not possible.

The process of writing and revising this book helped me (and Libby) realize that loving our bodies isn’t necessarily the goal. Our bodies don’t exist to be admired for their beauty, even by ourselves. They exist as a vehicle for us to engage with the world, to live our one wild and precious life and all the complicated, messy and beautiful experiences that come with it.

Maybe the goal is simply to accept our bodies. Accepting our bodies exactly as they are can feel like a radical act in our society. And that feels radically wrong, which is why it’s so difficult. It took writing a plus-sized character for me to see that in the world, and in myself.

Post a Comment