Newly discovered photographs of 1990s rave culture taken by the fashion photographer Terence Donovan shortly before he died are to go on public display for the first time.

The intimate shots of revellers lost in the sounds of the Que Club in Birmingham, a music venue graced by everyone from David Bowie and Blur to Daft Punk and Run-DMC, are thought to be some of the last photographs Donovan took.

Hidden in a drawer in Wolverhampton for 25 years, the images mark a “very unusual” shift in subject matter for the photographer, who made his name in the 1960s capturing “swinging London” and supermodels such as Twiggy and Jean Shrimpton.

“At the time he took these photos, he was still a photographer for Vogue doing fashion shoots and taking photos of rich and famous people,” said Jez Collins, curator of the forthcoming exhibit, The Que, which will show 10 of the 65 newly discovered photos at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery in April. “He would photograph people like Princess Diana and musicians like Jimi Hendrix and Ian Dury – but to my knowledge, he had never photographed a club environment and ordinary, everyday people.”

Donovan was approaching 60 when, in January 1996, he focused his lens on the dance and rave culture of the Que Club at the request of his son, a student at Birmingham University who DJ’d there. “He would have been completely out of his comfort zone in terms of the music, which had a pounding beat, with a lot of drugs being taken in the dark,” said Collins. “I think the subject matter and the building itself intrigued him.”

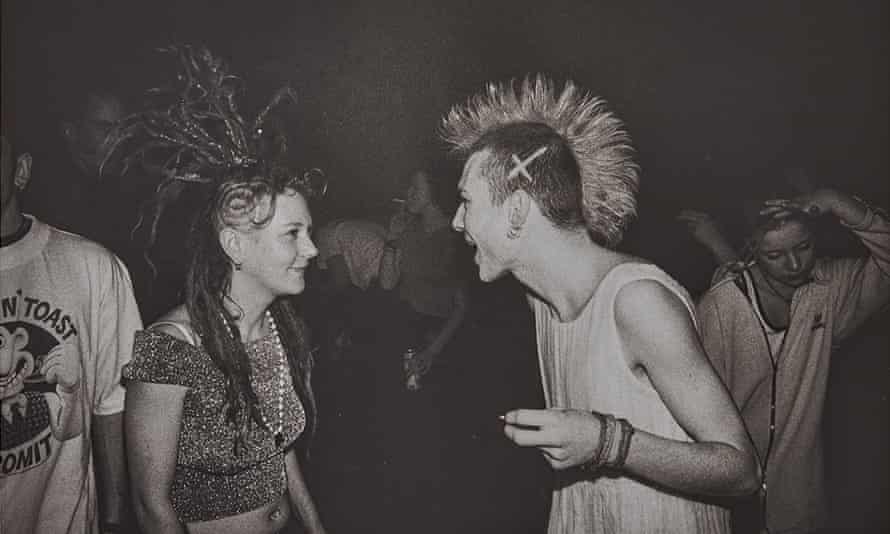

The Que Club was located in a former church, the cavernous Grade II-listed Methodist Central Hall, and Donovan visited on a techno music night known as House of God. Shooting in black and white, on a smoky dancefloor, “he captured something of great beauty. The photographs are really evocative of what clubbing culture was like then.”

As well as revealing the range of subcultures in the club – punks with mohicans, bare-chested skinheads, girls in tight dresses and youths in tracksuit tops, “these photographs show the intimacy of the dancefloor, the unbridled expression of people having a good time, of dancing together in a close space”.

They seem particularly poignant at this time. “I think people will look at this, when the exhibition is on, and just have that moment of thinking of things that maybe we have lost because of Covid,” said Collins. “That intimacy, that closeness, that experience of being very close to people you don’t know and sharing in that same moment the same music – and dancing together. That sense of being part of something bigger than yourself.”

Donovan’s photos highlight a culturally important moment in the history of Birmingham’s music and clubbing scene, he said. “It’s an amazing find after all these years. This was an important place for people, and it’s been captured by one of the greatest British photographers of the time.”

In November 1996, Donovan took his own life. At the inquest, it emerged he had been suffering from severe depression, linked to a steroid treatment prescribed for his eczema.

By then, his son had sent the pictures to Chris Wishart, a founder of the House of God club night. They lay in the drawer at Wishart’s house until Collins, founder of the Birmingham Music Archive, which documents and celebrates the city’s musical heritage, turned up last year to interview Wishart for a film about the Que Club.

“I interviewed him for an hour and a half and he didn’t mention Terence coming to the club or the photographs. But as we were walking out the door, he said ‘Jez, I think you might be interested in this.’ And I opened this drawer, and there was this box of Terence Donovan photographs. They were just stunning.”

He could hardly believe his eyes: “I actually took a photograph of the drawer.”

Post a Comment