At 17, with a couple of dollars in his pocket after a stint of choosing shiraz grapes in Mildura in north-west Victoria, future singer-songwriter Archie Roach walked out on to a freeway. He smoked three cigarettes and, to determine the place he would go subsequent, he tossed a 20 cent coin.

Heads would imply following the highway signal that learn Adelaide, the place he had by no means been. Tails meant returning to Melbourne, to meet up with his siblings. They'd been reunited years after state authorities had stolen Roach, aged three, and his brothers and sisters from Framlingham Aboriginal mission within the state’s western district, splitting them into separate foster houses.

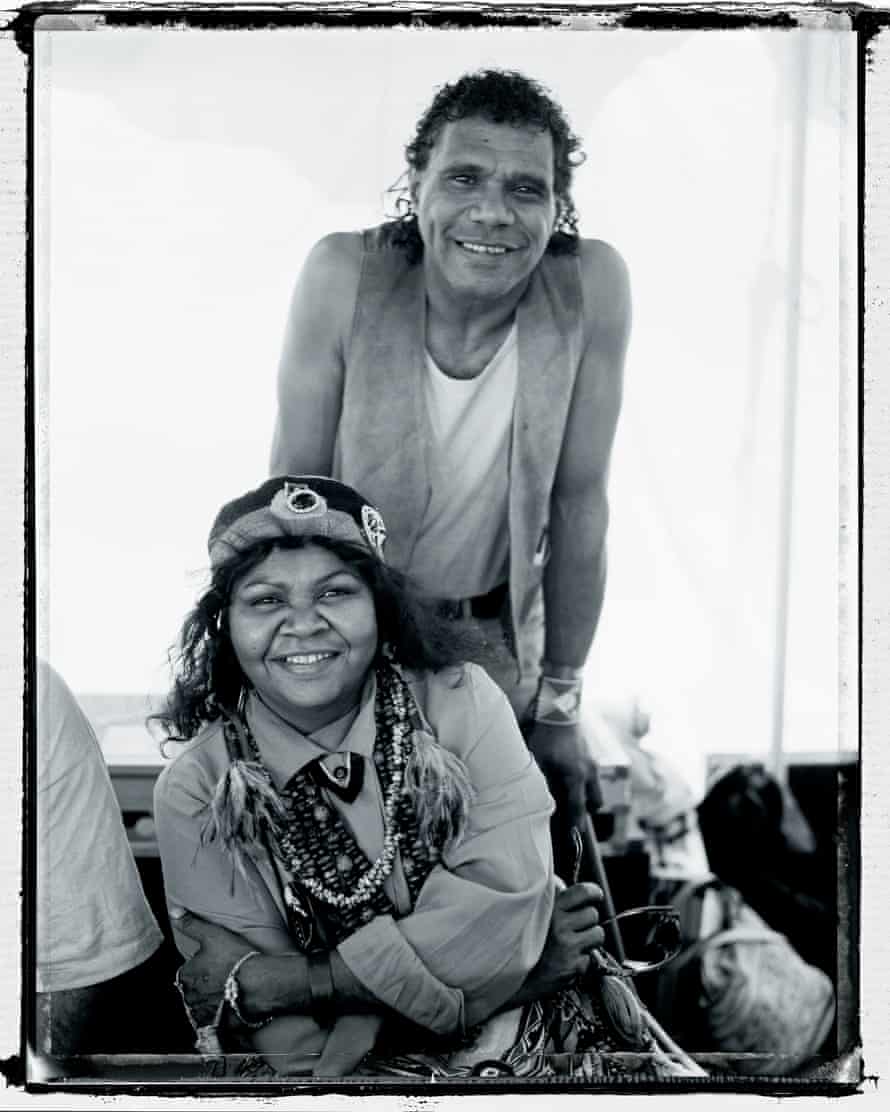

The coin landed on heads. Roach discovered lodgings with the Salvation Military in an ornate, late nineteenth century constructing in Pirie Avenue, Adelaide, often called the Individuals’s Palace. There he met Ruby Hunter. The tiny, extroverted Ngarrindjeri teenager was additionally trying to find her id after being stolen on the age of eight from her grandparents’ residence in south-eastern South Australia’s Coorong area. It might turn into a relationship that allowed them to save lots of one another.

Throughout Australia, frontier violence had given method to a brutal “safety” period by which the states assumed welfare management of Indigenous individuals, forcing many on to missions and reserves whereas usually eradicating kids. When he was 14 and in foster care, Roach, a Gunditjmara/Bundjalung man, discovered in a letter from his sister that each their mother and father had died. He would later write Took the Kids Away, launched in 1990, which might turn into an anthemic ode to those stolen generations.

Simply as Roach wrote of authorities who “gave us items to ease the ache”, Hunter and her siblings had been promised they had been going to the circus however had been despatched to kids’s houses and cut up up between foster carers. Roach would later recall in his track Previous So & So how when he met Hunter that day, “she couldn't cease speaking”.

Roach, now 66, who talks to Guardian Australia from his residence on his mom’s nation, close to Framlingham, the place he's Maar nation elder, was all the time the “shy” one. “I may speak to individuals in these days if I had a little bit of Dutch braveness,” he says. “On the time, she was the alternative of who I used to be.”

Their love story is the topic of writer-director Philippa Bateman’s new documentary Wash My Soul within the River’s Movement, to be launched in cinemas in March. In it, Roach and Hunter’s relationship is recounted within the songs they carried out collectively within the 2004 premiere of their Kura Tungar – Songs from the Riverconcerts with composer-pianist Paul Grabowksy and the Australian Artwork Orchestra, in addition to backstage and rehearsal footage and interviews, interspersed with footage of the Coorong.

“Archie is my silent hero and I’m his rowdy troublemaker,” Hunter says within the movie.

“She simply had this cheeky approach about her,” Roach recollects. “Not a lot making hassle however had this glint in her eye.”

The couple had many kids of their very own, together with sons Amos and Eban and foster kids Kriss, Arthur and Terrence. Unofficially they taken care of an additional 15 to twenty kids over time, Roach estimates, admitting that he’s by no means stopped to tally the quantity. I inform Roach I vividly recall interviewing the couple at their Melbourne kitchen desk in 1998, numerous kids dashing previous, and the way beautiful it was when Hunter stored calling me “bub”. “She’d welcome individuals wherever she was,” says Roach, “whether or not at residence or after we went across the nation.”

Once they started singing Took the Kids Away or one of many early songs Hunter penned, Down Metropolis Streets, which handled their homeless years preventing battles with alcohol, had been they acutely aware of opening viewers hearts to recognise shared historical past and fact?

“Individuals made us conscious by developing and speaking to us,” he says. “They mentioned: ‘We weren’t taught something about this in school, stolen generations and being faraway from households.’ There was nothing being taught about up to date Aboriginal individuals and their lives within the cities.”

Within the live performance featured within the new documentary, Hunter wears a headdress created from pelican feathers from her conventional residence in addition to rock cockatoo feathers amid raffia, sequins and mirrors. The pelican “is admittedly Ruby’s spirit”, says Roach. “Within the dreamtime she was a pelican, earlier than she got here to Earth and was born as a child woman. When she handed away, in fact, she turned a pelican once more.”

As Roach would sing on the finish of Took the Kids Away, the youngsters “got here again”. When as adults Hunter and Roach returned to the Coorong, “every thing simply got here again to her from when she was a toddler they usually had been taken. She simply wailed and hit the bottom. I felt responsible about taking her again there, you understand? I mentioned, ‘Oh, sorry I introduced you again right here, bub. We’ll go.’ She simply checked out me and mentioned, ‘Seize my footwear, I’ll stroll round right here barefoot.’” Hunter would die of a coronary heart assault, aged 54, in 2010.

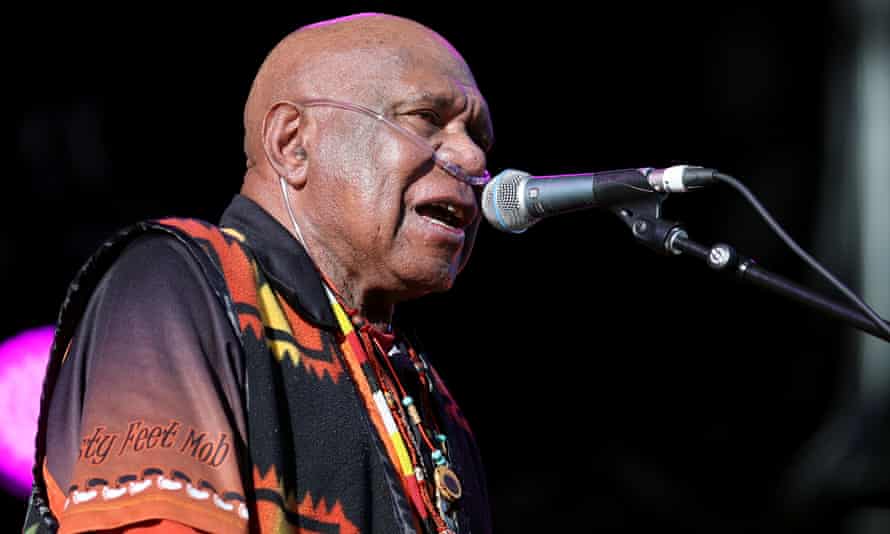

Roach’s personal well being has deteriorated. He has lived with persistent obstructive pulmonary illness for years and wears a nasal cannula to entry oxygen. In late 2020, an ambulance waited on standby outdoors a theatre, the place he was inducted into the Aria corridor of fame by way of stay telecast, to ferry him again to hospital, largely for statement. “I exploit oxygen a lot of the day,” he says now. “It’s one thing that helps me get by means of and do issues.”

Roach wrote philosophically in 2012: “My latest bouts of sickness, I’m positive, are a results of the Ache of being faraway from my household at a younger age and extra not too long ago the lack of somebody I beloved so dearly. However Ache may also result in change in a single’s life for the higher, we are able to select to disregard the Ache till it turns into insufferable or we are able to do one thing.”

The good news is that Roach is feeling properly sufficient to carry out in a free live performance with Grabowsky and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra on the Myer Music Bowl in February, and in April will undertake his final highway tour of New South Wales, with Queensland dates added. He plans to make extra albums and play extra concert events. “That is the final tour so far as getting on the highway, however I’ll nonetheless be doing exhibits wherever I can.” He has additionally been making Kitchen Desk Yarn vodcasts, giving a platform to younger up-and-coming music-makers.

Writing nonetheless alleviates ache, he says. “There’s a therapeutic energy in music and I realise that extra at the moment, I’m relying extra on that therapeutic. It’s a spot you'll be able to go to whenever you’re down and never properly, nevertheless it’s additionally a spot you'll be able to go to whenever you’re on high of the world.”

One Tune: The Music of Archie Roach is on the Sidney Myer Music Bowl on 19 February. Wash My Soul within the River’s Movement will likely be launched in cinemas throughout Australia from 10 March. Roach’s NSW and Queensland tour runs from 31 March to 23 April, with Adelaide and Perth concert events to comply with

Post a Comment