It looks like an inversion of the pure order of issues to be on Michael Crick’s doorstep. In virtually 40 years as a political reporter Crick has made the kerbside ambush of his topics, outsize furry microphone at hand, one thing of a private artwork type. Throughout his lengthy stints as political editor of BBC’s Newsnight and as political correspondent at Channel 4 Information it was stated that there was no extra alarming sentence for a authorities minister than “Michael Crick is ready for you outdoors”. For a choose few – Jeffrey Archer, Michael Heseltine, Michael Howard – these phrases have solely been eclipsed for anxiousness by “Michael Crick is writing your biography”.

Crick’s home is a pleasant double-fronted Edwardian terrace simply off Clapham Widespread, south London. He purchased it together with his mom, Pat, 31 years in the past, moved in together with her for some time when his first marriage ended and since her loss of life in 2010 has lived right here together with his accomplice, Lucy Hetherington (daughter of the previous Guardian editor Alastair), and their daughter, who's now 15. He greets me grinning and a bit stir-crazy from 10 days of asymptomatic Covid quarantine, the itinerant gumshoe confined to quarters. We sit at reverse ends of a settee within the bay window of a book-crammed by means of room. Crick, a boyish 63, is an obsessive collector not simply of uncomfortable information, however of a lot else in addition to. He has “nearly” (stated by means of gritted tooth) each Manchester United match day programme because the warfare. He additionally hoards political toby jugs. A lineup of the latter on his mantelpiece contains, prominently, the topic of his newest e-book, Nigel Farage, gurning in a spivvy swimsuit and a gangster’s fedora.

He had been considering of writing a e-book on Farage for seven or eight years earlier than he bought all the way down to it over lockdown. The primary little bit of digging he did again then was into the main points of a letter a trainer as soon as despatched to the top of Farage’s faculty, Dulwich Faculty, when Farage was proposed as a prefect, complaining of the long run Ukip chief’s “publicly professed racist and neo-fascist views”. In the midst of 300 interviews with Farage’s mates and enemies since then, Crick has pieced collectively the definitive portrait of a personality he describes as “essentially the most vital [British] politician of the century to date…” If that billing sounds, to liberal ears, like a deliberate provocation, Crick makes a robust case within the almost 600 pages of One Get together After One other. Farage emerges from Crick’s e-book each as the last word chancer – dishonest loss of life and political all-comers and wives and Eurocrats – and the instinctive disruptor of our political occasions, singlehandedly shifting each the main target and method of debate.

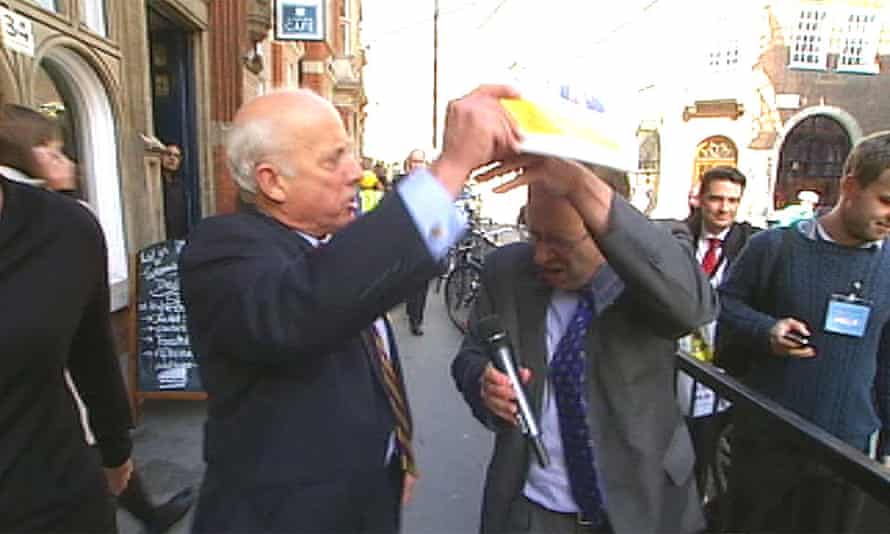

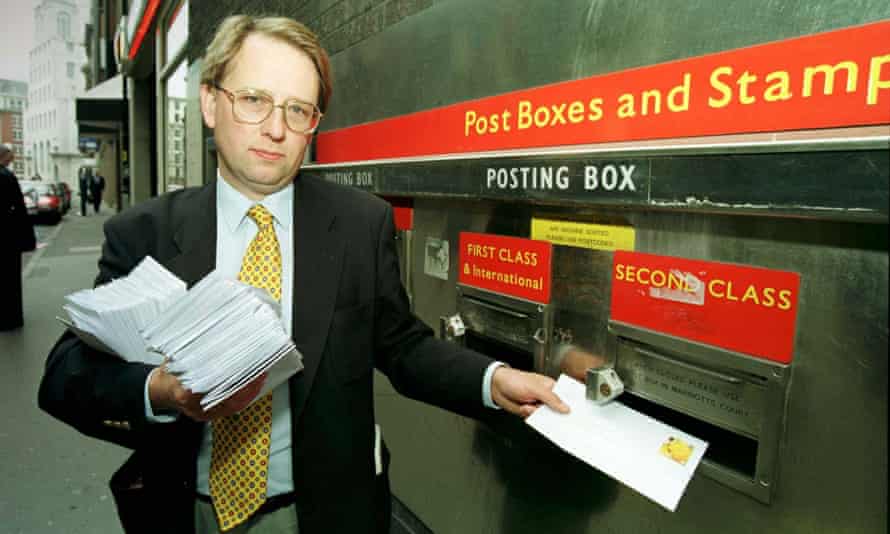

A few of Crick’s motivation is at all times setting the file straight, like a pissed off schoolmaster. “Farage has performed his personal memoirs twice, loads of which wanted correcting,” he says. After which, after all, he is aware of a narrative when he sees one. “He was at all times assured field workplace for a information reporter. You'll ask 5 questions, you’d get 5 nice solutions.” This was in distinction to a few of Crick’s extra tongue-tied political topics through the years, who've hardly ever been moved to talk even when our intrepid reporter has been chasing them alongside the pavement. (There are YouTube compilations of Crick’s greatest gotcha moments. His personal favourites, in no specific order, embrace the second he trapped Tony Blair in a elevate; the time MEP Godfrey Bloom bashed him over the top with a duplicate of the Ukip manifesto after Crick identified it contained no black faces; and his scrumptious line to the notably taciturn Iain Duncan Smith: “Aren’t you take this ‘quiet man’ factor a bit far?”)

Against this, Farage has at all times been comfortable to reply what Crick has thrown at him; he sees him as a consummate communicator. “Some, like Heseltine, are nice on the platform, however hopeless with folks. Farage can do each,” he says.

The early critiques of the e-book have fallen over themselves to reward Crick’s tireless data gathering, his peerless grasp of telling element, whereas expressing frustration at his refusal to go sentence on his topic. “Fairly how far-reaching Farage’s legacy shall be – how damaging or useful, or a mix thereof – it’s far too quickly to guage,” Crick writes. “It's too limp of the creator to not come to his personal conclusion,” Andrew Rawnsley instructed on this paper.

Crick rejects the argument that a reporter can ever be too even-handed. Given the load of proof, although, is there not a transparent case that Farage’s “breaking level” focus on immigration is damaging and harmful?

“Sure, after all,” he says. Earlier than persevering with: “I don’t suppose Farage is a racist, although there's loads of proof that he was a each a racist and an antisemite in his teenage years. And he does, I believe, like [his hero] Enoch Powell, pander at occasions to racists.” However, he says (there's at all times one other hand), “the problem of cross-Channel migrants, say, is a authentic difficulty and for a very long time no person else was mentioning it”. After which: “One good impact of Ukip is that it really took assist away and ultimately gained the battle with the BNP.”

Although he catalogues each dispiriting tactic in Farage’s power-hungry manipulation of populist sentiment, there appears to be rather a lot he additionally admires.

“I like his persistence and his vitality,” he says. “I don’t admire his pandering to racism, I don’t admire his ruthlessness. He was Stalinist in the way in which he ran Ukip. However clearly he does have a appeal. I’ve had some good laughs with him.”

The thread by means of Crick’s biographies, which started together with his meticulous and typically gleeful dismantling of the numerous lies of Archer, is that this fascination with excessive contradiction in sure personalities.

“I write about charming monsters,” he says. “I believe two-thirds of actually profitable high-achievers are charming monsters. Alex Ferguson [the highly reluctant subject of another Crick book] is an ideal instance. When he's charming, he’s a delight, completely considerate and thoughtful. And but he will be an absolute bastard, completely ruthless, minimize off individuals who had been his mates, precisely as Farage has performed. That mixture has taken many individuals to energy. I’ve little doubt even Hitler, Stalin and Saddam Hussein had sure charms.”

Does he suppose writers are drawn to clarify the points of interest of human behaviour they worry or lack in themselves?

“I suppose so,” he says. “Are there features of me which might be like a few of these folks? Effectively, in very small methods. I can definitely be very tough at occasions.” He hoots with one among his frequent, likable self-deprecatory laughs. “I’m unsure many individuals would establish any appeal.”

One other a part of the attraction of Farage as a topic, I believe, is that it gave him an opportunity to say “I informed you so”. Like anybody with a background outdoors the south-east of England – Crick did a lot of his rising up in Manchester – the Brexit referendum consequence got here as little shock to him.

“About three weeks beforehand, I used to be telling those who Brexit was going to win,” he says. “However I don’t suppose a lot of my colleagues at Channel 4 Information – or on the BBC – believed it, as a result of they primarily combined in liberal circles and so they didn’t need to know that there have been huge numbers of individuals on the market who had severe misgivings about immigration and about Europe.”

That type of wishful myopia, he suggests, is likely one of the causes he lately determined to finish his 10-year stint at Channel 4 and take up a job on the Day by day Mail’s “in depth” Mail+ challenge, contributing a characteristically entertaining and knowledgeable weekly on-line video report, in addition to a Friday column.

“I ended up having arguments [at Channel 4],” he says. “Below the then editor [Ben de Pear], I felt the programme was on an anti-government, anti-Brexit campaign. It made it very tough to do your job. And to me it was unsuitable. I used to be introduced up within the custom of David Nicholas, who was editor of ITN once I first joined 40 years in the past, and who simply turned 91. He used to say, ‘If we get an interview with God, then the very first thing the newsdesk has bought to do is get on to the satan’s workplace and provides him the precise to answer’.”

It appears perverse to reply to that perceived partisanship to take up a job on the Mail, the information organisation that arguably has performed most to polarise debate earlier than and because the EU referendum. Was one of many points of interest giving two fingers to the “liberal institution”?

“No,” he says. “The attraction was it [Mail+] was a brand new enterprise. They usually got here alongside and supplied me this nice job.”

Good cash?

“Sure and for 2 and a half days every week. It’s bloody laborious work. For the primary time in a very long time I don’t have a producer, so I do all of the movies by myself, however I've loads of enjoyable and whole freedom.” The pliability additionally allowed him to commit extra time to his e-book and to indulge his anorak’s ardour for constitutional politics by serving to to arrange a tutorial unit at Manchester College, which can monitor the choice means of MPs.

Crick has been a political animal for so long as he can bear in mind. His dad and mom, each academics, met after they had been each officers on the socialist membership at Cambridge College. His father gave up that trigger, however his mom, who collected miners’ badges in previous age, remained dedicated. “She died earlier than Corbyn got here to prominence, however she would have been a giant Corbyn supporter,” Crick says. “Whereas my father’s politics are actually rather more like mine, extra centrist and a bit cynical.” Crick describes Boris Johnson as “simply the worst prime minister in 100 years”. However he additionally tends to agree together with his previous man “that in case you suppose the Johnson authorities is incompetent, then a Jeremy Corbyn authorities would have been 10 occasions worse”. Crick’s first e-book, on Militant tendency, stays the seminal account of how a fringe political drive can manoeuvre itself into energy. His plan was at all times to enter politics, however when he was supplied a transparent run on the secure Labour seat of Bootle in 1990, he declined, acknowledging “it was extra enjoyable to be a journalist”.

Crick was a scholarship boy at fee-paying Manchester grammar faculty, the place he wrote “the Fifth Column” for the college journal. A number of of his political friendships had been shaped at Oxford, the place he was editor of the coed newspaper Cherwell and president of the Oxford Union (in addition to gaining a primary in politics, philosophy and economics). Listening to him speak about these years is to be reminded of the incestuousness of Westminster. He was a up to date of former Tory ministers Dominic Grieve, David Willetts, Damian Inexperienced and Alan Duncan. As union president, he succeeded Philip Could, whose girlfriend, the lately graduated (and “very glam”) Theresa, spoke at his first debate. She was one among three acquaintances who grew to become prime ministers, together with Malcolm Turnbull in Australia, with whom he retains in contact, and Benazir Bhutto.

What does he take into consideration that apparently indestructible conveyor belt to energy?

He thinks each that it’s inevitable – Oxford has at all times attracted an mental elite – but additionally that its affect is waning. He has in any case at all times tried to take care of a scrupulous distance from politicians.

“I’ve had a handful of mates who're politicians – I used to go to soccer matches with Chris Grayling – however the quantity who’ve been right here [to Clapham] in 30 years might be about three. I’m a bit like Farage in that respect; I regard myself as a kind of anti-establishment particular person and but I need to be inside it in a approach. I’d by no means be part of a gents’s membership, however I’m not averse to going to them. I do the previous boys’ column for the college journal.” He offers one other of his frequent hoots of self-mockery. “There may be,” he insists, “an extended custom of multinational revolutionaries.”

A number of the most fascinating materials within the new e-book is Crick’s account of Farage’s formative relationship together with his dad and mom: the alcoholic stockbroker father and the mom who was a really enthusiastic nude mannequin for the Ladies’s Institute in Surrey. If you happen to had been to hunt related insights into Crick you'd little doubt need to dwell on the 2 sticking factors of his childhood: his inevitable marginalisation inside the household after the arrival of triplet sisters and the truth that his dad and mom cut up up when he was 18. “I carried on dwelling with my father within the holidays; my three sisters went to reside with my mom,” he says. His father was “very rather more educational” than him and a rugby man somewhat than a soccer fan. A part of Crick’s rebellious streak noticed him observe his beloved Manchester United, residence and away from in regards to the age of 12, hitchhiking alone or on the practice; he as soon as tried to have his title modified to George Crick in honour of his hero, George Finest. When Rupert Murdoch’s BSkyB tried to take over the membership in 1999, he took months off from Newsnight to work on a (profitable) rearguard motion.

There was in his early journalism a robust sense of ethical outrage about him. He was, by the accounts of contemporaries, a pure within the function of the martyred messiah in a college thriller play. I bear in mind masking Jeffrey Archer’s perjury trial for the Observer. Nonetheless early I arrived in courtroom, Crick, his pencils metaphorically sharpened, would already be in place. You wouldn’t say he has misplaced his edge since then, however maybe turn out to be extra alive to instances for the defence.

I remind him of one thing he stated to the Telegraph in 2007 not lengthy after his marriage ended following his admission of an affair. The interviewer puzzled if these occasions made him really feel extra sympathetic in direction of Archer? “Sure, I suppose so,” Crick answered on the time. “Certainly, to folks normally. Ten years in the past, I'd have been horrified by the concept that I'd have had an affair and I wouldn’t have been very understanding with myself. I'm much more understanding of individuals when that occurs.” Studying his present e-book, I sense that empathic impulse has superior with age?

“Effectively,” he says, “sure. Life is definitely difficult. And Farage is a case the place his life has been very difficult. As with the prime minister, his affairs are a part of the political story.” (Or as one quoted aide to Farage places it, much less delicately within the e-book: “He’d shag something that permit him.”)

If Crick stays fascinated by recklessness, he additionally is aware of that tales by no means finish when the cameras retreat. I’m not stunned to find he sees all the topics of his books as lifelong tasks. He religiously retains up with Archer’s novels, for instance. When he noticed Archer, a person he did greater than anybody to incriminate and in the end incarcerate, lately at a e-book launch, he couldn’t resist sidling as much as say howdy. He has lengthy coveted a plan to make a radio documentary in regards to the novelist and his conman father (and Archer’s “unknown” half-sister, a baroness who was married to an American presidential candidate). What did he say?

“Effectively,” Crick remembers, laughing, “I stated, ‘I do know you and I’ve had our variations, however can I take you out to lunch?’” Archer didn’t say no outright, so Crick believes it would occur.

I sense he half-fears, half-relishes the concept that he would possibly discover himself in the same type of long-term dance with Farage. “I used to be,” he says, “a bit unhappy that I needed to end the e-book ultimately.” He felt there have been nonetheless issues to find, not least maybe just a little extra about Farage’s curious relationship with Julian Assange, which Crick examines with out ever fathoming. He has little doubt that there shall be dramatic future chapters in Farage’s profession (he factors to a ballot he found that instructed 54% of Tory get together members would favour him as their subsequent chief). That’s the opposite factor about these charming monsters, nevertheless a lot you expose them to the sunshine – and nobody works tougher at that illumination than Crick – they don’t merely disappear. They invariably come again for extra.

Post a Comment