Music writing has come a great distance because the days of the inkies – the papers that would go away marks on their readers’ fingers – when a handful of male gatekeepers dictated the tastes of Britain’s music-loving teenagers. Whereas feminine writers had been sometimes admitted to this hallowed membership, they had been the exception slightly than the rule. Since then, the music press has been directly democratised and straitened by the arrival of free content material. Beforehand marginalised voices are actually being heard, even when the charges of pay are largely paltry.

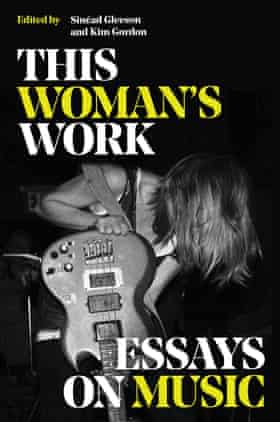

This Girl’s Work, an anthology of 16 essays by feminine writers compiled and edited by Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon and the critic Sinéad Gleeson, is a piquant reminder of the expertise, musical and literary, that has at all times been beneath editors’ noses, if solely they cared to look. Billed as a “problem [to] the historic narrative of music and music writing being written by males, for males”, the contributions cross genres, a long time and continents, and are much less about casting judgment on artists and their work than the method of discovery and the methods music can affect and enrich lives.

The most effective of those items alight on the intersection of music and identification, and the way politics and private relationships are sometimes intertwined with our listening. The American novelist Leslie Jamison’s Double-Digit Jukebox: An Essay in Eight Mixes is constructed round mixtapes and divulges how the creator spent her childhood experiencing music by way of the preferences of the lads in her life, from her older brother to mates and companions. For her, music was sure up with male approval, although this adjustments as she forges a life and identification of her personal. As a single mom locked down together with her daughter within the early months of the pandemic, she listens to previous songs with contemporary ears and finds them reworked.

The creator Fatima Bhutto, niece of the previous Pakistani prime minister Benazir Bhutto, reveals her childhood homesickness for a land she had by no means visited. This longing was handed down from her father, the politician Murtaza Bhutto, who, exiled from Pakistan and residing in Syria, was eternally telling his daughter that they might return quickly. He would play Otis Redding’s wistful (Sittin’ on) the Dock of the Bay, a couple of man removed from house and Ho Jamalo, a Sindhi people tune performed at weddings and events. Music, she recollects, “carried us over the swells and tides of loneliness”. In the identical essay, Bhutto additionally examines music as a method of resistance: Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Noor Jehan and Fela Kuti are among the many artists to have stood as much as oppressive regimes. “Tyrants concern music,” she observes, “as a result of irrespective of their drive and their energy, they'll by no means, not ever, have the ability to management what is gorgeous.”

Grief, whether or not for the lifeless or for the previous, is a recurring theme, with music concurrently providing consolation and re-opening previous wounds. The London-based author and broadcaster Zakia Sewell reveals cassette recordings of her mom, since devastated by psychological sickness, as a younger girl singing in an acid jazz band. “She sounds completely happy,” Sewell displays, “however there’s one thing telling in her vibrato, in the way in which it swells and quakes. My mom: a ghost, immortalised on tape.” Writer Maggie Nelson’s vivid and heartfelt My Good Buddy recollects her childhood friendship with the Mexican-American singer Lhasa de Sela, stalwart of the all-female music pageant Lilith Honest. Nelson had way back misplaced contact with “my first and solely really bohemian good friend” when she discovered, in 2010, that she had died from breast most cancers. Her essay is a visceral account of feminine adolescence and the ebb and circulate of friendship in addition to a shifting epitaph for a fancy, charismatic and typically maddening artist.

Elsewhere, Jenn Pelly writes on Lucinda Williams’s Fruits of my Labor, describing it as “a requiem, a street tune, an escape hatch, a poem”; Juliana Huxtable composes a febrile, if sometimes impenetrable, “reward poem” for Linda Sharrock, main gentle of Sixties avant-garde jazz; Margo Jefferson seems on the lifetime of Ella Fitzgerald and the a number of methods she was cruelly judged; Rachel Kushner traces the early profession of Wanda Jackson earlier than she discovered sobriety and God; andYiyun Litells of her relationship with Auld Lang Syne, which for her is greatest sung in July. Gleeson’s personal essay pays tribute to the composer Wendy Carlos, the criminally ignored mind behind The Shining soundtrack and extra; whereas Kim Gordon has a dialog with the Japanese artist Yoshimi P-We, drummer within the Boredoms, in regards to the purity of self-expression.

If this all sounds a little bit severe, let me level you in direction of the Irish novelist Anne Enright whose Fan Lady finds her reflecting on the “lovely catastrophe” that unfolded in the future in New York when she met the artist and musician Laurie Anderson. Enright’s mind instantly appeared to disengage from her mouth, rendering her incapable of claiming something aside from “a single gloop of word-sentence-blurt”, which she renders as “fiffloopidiggllyblop”. She might have didn't kind coherent sentences in Anderson’s presence, however she makes up for it in a vigorous and entertaining piece that paints the artist as a trailblazer, mischief-maker, kindred spirit and private hero whose haircut Enright flagrantly copied. Because the title suggests, the creator makes no bones about being a “fan woman”, a pejorative time period invariably used to separate severe male musical appreciation from music-loving women supposedly pushed by idolatry. Enright notes how she has strived to keep away from what she calls “the music dialog, the one the place individuals collect into tribes, swap favourites, choose, embrace, exclude, bond, declare standing or coolness or an identification due to their decisions. Music undoes me. It doesn't inform me who I'm.”

Judging by the opposite essays on this e-book – the title of which is taken from the Kate Bush tune – you sense that Enright is just not alone in rejecting musical tribalism and perceptions of what is likely to be cool or in any other case. What binds these writers is their emotional connection to music, and their expertise of songs as a portal to recollections – whether or not painful or joyful – and a broader understanding of the world. This Girl’s Work is a group of music writing, however within the loosest potential sense. Right here, music is the soil through which all method of tales take seed and bloom.

Post a Comment