With detailed research of flaking, iron-blooded rock, printed at monumental scale Ingrid Pollard directs our ideas to the larger image. The title of her present, Carbon Slowly Turning, may describe the movement of the spinning Earth, with you, me, the bushes and different carbon-based life upon it.

However Pollard’s urge to revisit and remix artwork made throughout 4 a long time additionally makes me consider a compost heap – in a great way. The present concludes with a few of her oldest work – physique photographs from 1991 articulating lesbian expertise – alongside her most up-to-date, pleasure, propaganda and nationwide id. It’s as if Pollard is consistently turning her pile of leaves, pulling outdated materials by new, to see what mycelium it would generate.

Pollard is, primarily, a photographer, and as with Wolfgang Tillmans, is within the qualities of the photograph as an object, and the way modes of presentation can remodel the way in which we learn a picture. Reverse the doorway hangs a row of silvery images of a wind-scoured part of British coast: The Boy Who Watches Ships Go By. Right here, weather-bleached wooden protrudes from pebbles like outdated bone; the hull of a ship exposes its scraped age above the shingle; a lighthouse is spied throughout islands of silt. Hand-tinted, printed in a blotchy, painterly method on canvas, the images attraction to melancholic nostalgia.

The watcher right here is Pollard, staring by the viewfinder, and scrutinising prints within the darkroom. However as two fragments of 18th-century textual content printed above the images point out, the watcher can also be an African little one, lengthy lifeless, who as soon as performed the fiddle as “Captain’s boy” on a ship loaded with human cargo, travelling between the Gambia and Jamaica.

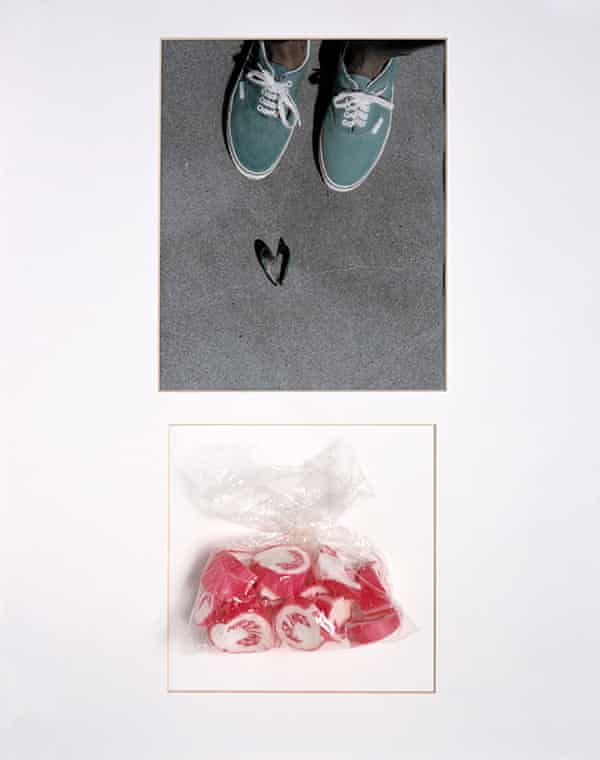

Glimpsed portraits of the artist in Hastings (Seaside Collection, 1989), are framed with sticks of rock and souvenirs, above scraps of textual content referring to the final profitable invasion of Britain, and different types of intrusion (“… and what a part of Africa do you come from?”) Pollard is all in favour of aesthetics of the coast, however she’s additionally all in favour of Britain’s lengthy sea border as a spot of departure and arrival, whether or not you come as a vacationer, an invader, an enslaved servant, or a migrant.

The standout work right here is Seventeen of Sixty Eight (2019), which artfully matches conceptual enquiry to Pollard’s curiosity in how visible data is displayed and dispersed. Via objects and footage of many sorts – colourless photographs embossed on white paper, facsimiles of redacted e-book pages, steel tokens, stained glass, pub indicators – she drags the deeply embedded historical past of African our bodies in Britain into view. The websites in her images are unremarkable – rural inns, suburban lanes, tracts of countryside – but all bear a title referring to a “Black Boy”. Somebody – or some incident – touched every place in a method that left a reminiscence of an individual (although not their title) as a marker.

In amongst these artefacts and pictures is a lone photograph of a grotesque blackface “minstrel” marionette. A neat white field sits on a neat white plinth in among the many signage and statuary within the centre of the gallery. Click on open the doorways and music leaps from inside: a video through which the minstrel puppet dances to your eyes alone. Shut them once more and, like a jack-in-the-box, he's hidden from view. As ever with Pollard, the mode of show may be very explicit: there’s one thing obscene about this whole gadget.

The title – Seventeen of Sixty Eight – is left unexplained, although it tells us we’re solely seeing a fraction of a bigger image. An earlier model was proven at Baltic in Gateshead, after Pollard was chosen for the 2019 Baltic Artists’ award. This was the primary in a victorious hop skip and soar for the 69-year-old artist. The exhibition at Milton Keynes is the results of Pollard’s receipt of the 2020 Freelands award for mid-career girls artists. This present in flip has garnered her a nomination for the Turner prize.

Continuing by the exhibition, it turns into more durable to disregard what sound like significantly grating constructing works close to by. Moving into the ultimate room, we meet the supply of the noise: Bow Down and Very Low – 123 (2021), a trio of kinetic sculptures, two of which (a pair of bending, scraping steel saws, and a physique of knotted ship’s rope) seem to genuflect, and the third of which impotently swings a baseball bat. Behind them is a row of lenticular prints of slightly Black lady in a white Forties gown, trapped without end as she bobs out and in of a curtsy.

As a central room exploring portraiture and narrative attests, Pollard is a charming photographer, however there are a lot of layers of enquiry happening past the floor seduction. This isn't simple artwork – it doesn’t include a neat punchline. I believe even for the artist, associations shift with each flip of the compost heap.

Post a Comment