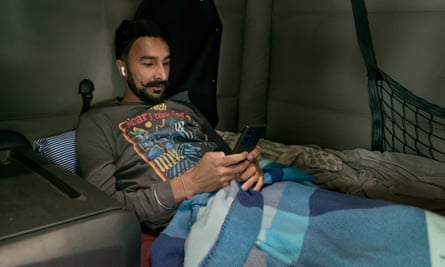

After spending an evening in late September driving an 18-wheeler throughout the nation, Gurpreet Singh woke as much as see his telephone lit up with notifications from US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Instantly, Singh known as again to acknowledge the contact makes an attempt. Then he snapped a selfie to add into the cellular app immigration officers used to trace his whereabouts.

Earlier that morning, worn out from a nonstop 11-hour journey that began in Bakersfield, California, Singh, a Punjabi immigrant awaiting asylum, had gotten the time zones confused. When the notification he anticipated didn’t arrive, he merely submitted an unprompted selfie and fell right into a deep sleep. As his co-driver continued the journey from St Louis to Chicago, the primary notification arrived, adopted by a flood of others, together with missed calls from a cousin whom Ice had contacted whereas trying to find him.

Already pressured about delivering his load on time, Singh now grappled with the worry that this error might harm his immigration case.

4 years in the past, Singh left his village in Punjab, India, flew to Mexico and crossed the US border, the place he was instantly apprehended, detained for 5 months, and launched on bond to await an asylum listening to. After six months, he utilized for a short lived work allow and shortly started working as a truck driver, hauling fruits, greens and meat backwards and forwards between his house in Bakersfield, California, and numerous east coast locations.

Two years in the past, nonetheless, an immigration choose denied his asylum case and issued a deportation order. Singh filed an enchantment and was granted one other listening to, scheduled for subsequent 12 months.

Within the meantime, Ice continues to surveil Singh by numerous means, from automated telephone calls to in-person appointments that generally conflict along with his load supply schedule. Not too long ago, Singh informed me, immigration officers put in the BI SmartLink app on his telephone; he defined that in a two-hour window on a preset morning every month, the app prompts him to add a selfie that's then run by facial recognition know-how.

For Singh, 27, navigating the labyrinth of the US immigration and asylum processes means adapting his life and work to take care of fixed and crushing uncertainty. However he refuses to let himself entertain the potential of deportation.

“Negativity does come into my thoughts, particularly when all routes appear to shut up,” he mentioned, talking in Punjabi. However his spirits rise when he listens to recordings of Gurbani, the Sikh scripture.

One morning this summer season, Singh drove into the scorching desert east of Bakersfield, his truck’s trailer loaded down with peaches. Earlier than beginning, he freshened up, inspected his truck, and ready a powerful batch of chaa on a transportable gasoline cylinder to gas him for the drive throughout the nation.

At one of many Punjabi truck stops simply off the freeway, he picked up two dozen rotis, sufficient to final him by the week. To maintain alert, he prefers to remain a bit hungry, typically consuming just one full meal a day. “If I eat an excessive amount of, I’d go to sleep,” Singh informed me.

For months, he’d been working 70 hours per week on common, taking quick breaks between journeys and incomes as much as $9,000 a month. He was saving as much as begin a life along with his fiancee, who lived in Punjab and was making use of for a US visa. That they had not seen one another in practically half a decade. In the meantime, he despatched cash to his household at any time when they requested. As political tensions rose in Punjab, Singh was additionally saving to assist pay for his youthful brother’s imminent journey to the US; as soon as settled right here, he too hoped to turn into a truck driver.

Truck driving has turn into a well-liked line of labor amongst Punjabi migrants at a time when the business faces driver shortages. Raman Dhillon, who leads the North American Punjabi Trucking Affiliation, estimates that a couple of third of truck drivers in California are Punjabi. Amongst these drivers, he believes that as many as 40% are undocumented and going by immigration proceedings.

Migrants from India represent the most important inhabitants from outdoors the Americas to cross the US-Mexico border. An exodus out of Punjab started within the Eighties and 90s, on the top of pressured disappearances, state-sanctioned violence and extrajudicial killings concentrating on Sikhs in India. Within the a long time since, migration has been fueled by the reverberations of intergenerational trauma, compounded by different components, together with continued political persecution, unprofitable farmland, bleak financial prospects and a drug epidemic. In California’s Punjabi trucking group, Singh finds an unlikely semblance of house. For him and his fellow migrants, a shared language and sense of apna-pan – kinship – present a buffer in opposition to the loneliness and disorientation of labor in a brand new nation.

4 years in the past, on the evening after he was launched on bond from the Imperial regional detention facility in Calexico, Singh and I sat within the backseat of a automotive headed north by the boulder-covered mountain ranges of San Diego county. Earlier that day, we had met on the El Centro Gurdwara, 15 miles from the border, a Sikh home of worship the place Singh had spent the day volunteering locally kitchen and making tearful telephone calls to members of the family, saying the excellent news of his launch.

Searching along with his brow pressed in opposition to the fogged-up window, he realized he was seeing the celebrities for the primary time in practically 5 months. “This appears like a second life,” he turned to me and mentioned, buoyant. Singh, who's tall and lanky, was carrying a darkish turban and a protracted beard that flowed to his chest, articles of the Sikh religion he’d stored since boyhood. Strapped above his shoe was the cumbersome ankle monitor he’d put on for the following two months.

He stayed at his aunt’s house in Bakersfield and, over the following few months, he labored additional time at eating places, truck restore retailers, and selecting greens on a farm, getting paid in money underneath the desk and making under minimal wage. Then, after his work allow arrived, he took truck-driving classes and began working, initially for employers who underpaid him for the miles he drove. Ultimately, he was capable of finding work that paid honest wages. “In jail, we are saying that we’ll be freed from our tensions as soon as we’re launched,” he mentioned. “However that’s when the actual tensions start.”

Close to the top of this summer season, his fiancee’s visa software was rejected, shattering the desires that had sustained him for years. Days later, Singh’s truck broke down after an oil leak wrecked its transmission, forcing him to overlook two weeks of labor. Shortly after he resumed work, Singh needed to test himself into an emergency room after he acquired sick from consuming spoiled rotis. A day later, he was again on the street.

He prefers driving over staying on the home he now rents with six different Punjabi migrants. Driving tires him out sufficient in order that he’s in a position to sleep effectively, and it retains him on a gentle observe, serving to him keep away from the intrusive ideas and worries that generally derail him at house. “If you dwell on the truck, you already know that you simply’re going to drive, you’re going to ship the load,” he mentioned. “You recognize you simply have to get by your miles.”

Life on the truck has modified him, emotionally and bodily. Since changing into a driver, he’s shed his turban and minimize his hair and beard for the primary time in his life, a choice that originally made him really feel unusual – virtually alien to himself. However dwelling on the street for days at a time, typically pressured to forgo common showers, he mentioned he discovered it troublesome to keep up these articles of his religion.

Throughout WhatsApp video calls along with his household, Singh listens to their tales whereas he calculates the timing of his stops and watches the street, his eyesight strained by hours of looking at dimly lit highways. Till his immigration case is accredited, as he hopes will probably be, Singh can't depart the nation to go to household elsewhere on the planet, nor can he carry relations to the US. As he seems forward, the years it would take earlier than he can get everlasting papers appear to recede into an incomprehensible distance.

Given the document variety of pending immigration court docket instances, migrants who discover themselves caught in limbo cling to the possibility to work regardless of the unsure future they face. There's presently a backlog of 672,000 asylum instances in immigration court docket, and about 133,000 of these are in California. Nationwide, in fiscal 12 months 2021, greater than 600,000 asylum seekers whose instances had been pending utilized for authorization to work as they wait.

At house in Bakersfield throughout a break between hundreds, Singh posted a video on social media together with photos of himself and members of the family, a few of whom have died within the years since he left India. It was set to the brand new Punjabi track Challa Mud Ke Nahi Aaya, which roughly interprets to “the beloved one by no means returned”.

Hundreds of different movies set to the track have been posted on Instagram and TikTok by different Punjabi migrants, somber movies knitting collectively a type of digital folklore, documenting suitcase-flanked household goodbyes and airplane takeoffs, hard-hatted selfies at building websites and solitary photoshoots in entrance of vehicles, displaying automobiles parked within the shadow of rugged cliffs, or ready within the rain for hundreds, or pointed towards lengthy, slender roads stretching past visibility. Inscribed on the movies are lists of years paired with flag emojis, temporally and spatially mapping the space from house.

“Once I hear that track,” Singh informed me, “the feelings, the ache in my coronary heart, all of it comes out.”

Ravleen Kaur is a multimedia journalist based mostly in Portland, Oregon. Her reporting focuses on migration alongside the intersections of race, gender, energy and coverage

Post a Comment