There's a bottomless black gap within the Royal Academy’s colossal survey of South African artist William Kentridge. It seems on display screen, a seething, gaping disc that circles and swirls, often flecked with a dot of sunshine to point some limitless passage downwards. It's nothing greater than an animated drawing, and the only factor right here, but it represents two terrors directly: our frequent worry of falling, and the total horror of sweated labour down a mineshaft.

Kentridge (born 1955) is the best and ingenious animator in worldwide artwork, the polemical chew of his charcoal traces operating all the way in which again to Goya, Daumier and the German expressionists. His method – neither imitated nor surpassed – is acquainted by now but by no means ceases to mesmerise. As an alternative of the successive drawings, one to every body, that make up most animations, Kentridge has for a lot of many years labored with a single picture for every scene that's drawn and redrawn, erased and altered utilizing charcoal and a rubber.

These drawings have proliferated into etchings, linocuts, animations, shadow performs, operas, ballets, tapestries and mechanical puppet exhibits – all represented on the RA – however they're the origin of all the things he makes. It feels perfect, subsequently, that the present opens with solo portraits of recurrent characters.

Listed here are drawings of the white industrialist Soho Eckstein, who lives off the sweat and blood of Johannesburg’s impoverished black residents, their faces urgent sturdy and near the image airplane. Right here is his uncared for spouse, Mrs E, and her someday lover Felix Teitlebaum, a stocky, balding artist with greater than a faint resemblance to his alter ego Kentridge, typically portrayed bare and from behind.

The world Teitlebaum turns to take a look at is all over the place seen: brutalised miners, queues of ravenous residents, police, canines, howling hyenas, the anonymous puppet-masters of the apartheid regime. And he himself is ubiquitous, typically as a watchful eye, typically as a ghostly define. You see him traced in an animated reprise of Alfred Jarry’s fat-bellied despot Père Ubu, the place he's now translated into Pa Ubu of the key police unit who tortured their victims. Kentridge’s father was a number one defence lawyer for black South African leaders, representing Nelson Mandela and the household of Steve Biko. The artist has a humble and intensely complicated sense of his personal position as a political artist.

However mordant as these solo drawings are, they collect true power via motion. Kentridge’s movies have a unprecedented surge and drag to them, every determine seeming to maneuver via the heaviest of instances, pulling the previous together with them – actually, by way of all of the earlier drawings, typically spectrally obvious. Eckstein lowers his eyes and the entire tone of a scene slowly sinks to despair and guilt. Teitlebaum turns to gaze on the room round him, his nervousness filling the home like darkish water.

Photos tremble and shift within the fluid density of the charcoal marks. Crowds construct, mill, march via a panorama in a single highly effective continuum. Eckstein buys up half of Johannesburg and the impact is brilliantly expressed as one thing like a flip of a web page on the display screen, wiping out each signal of life you noticed earlier than.

Cigar smoke turns into speech, fax machines churn out cash. Kentridge’s transitions are riveting. In the newest movie right here, Metropolis Deep (2020), Eckstein seems to be down into what he believes is an open grave, solely to find a miner digging one other bottomless shaft beneath. And all the understanding of European artwork vanishes earlier than his eyes within the museum: the work merely disintegrate, cascading from their frames like soot from a fire.

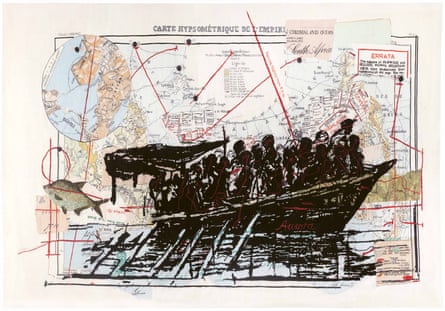

However what all of it means is getting tougher to parse, significantly since few of the early masterpieces are included right here, comparable to his epochal Historical past of the Major Criticism, an animation that quantities to a political compass. It's as if the grandeur of the Royal Academy elicited a response primarily based largely on scale. A excessive central gallery has been was a full-scale cinema for big projections. One other is crammed with Kentridge’s Colonial Landscapes, huge drawings that pastiche Victorian pictures of Africa to no sharp impact. A 3rd is hung with tapestries of his black and white collages labored in mohair from angora goats farmed within the Jap Cape. Meticulous as they're, these weavings totally lack his contact.

Kentridge is so prolific that he might have stuffed the RA many instances over; as it's, he has coated each obtainable inch, making charcoal drawings immediately on the partitions. But this choice appears virtually too well mannered in its nod in direction of Europe. A room of monumental roses and lilacs drawn on sheets of newspaper characterize an outsize homage to the late nonetheless lifes of Édouard Manet (Kentridge reprises Paul Nadar’s well-known photograph of Manet, suave in his wasp-waisted jacket, to stress the purpose). And you will notice hints of Dada, surrealism and constructivism all over the place, significantly within the props and stage units for performances.

Collaboration has all the time been Kentridge’s modus operandi,and these days the occasions have grown ever bigger. His opera productions have included Shostakovich’s The Nostril and Mozart’s The Magic Flute, although alas these experiences stay offstage. Compelled into Covid lockdown, there's a sense that Kentridge has been residing inside his personal head. He actually exhibits himself there, a ruminative determine, strolling backwards and forwards contained in the animated pages of a ebook.

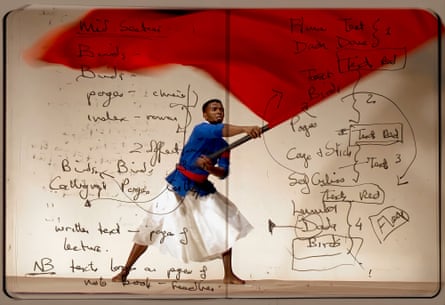

However it all comes collectively within the magnificent, multiscreen Notes In direction of a Mannequin Opera, which is nothing lower than a torrential storm of pictures throughout three screens. The title refers to Madame Mao’s mannequin operas, the one formally sanctioned state music permitted in the course of the Cultural Revolution. And what you see is equally stylised in its approach: drawings of birds in flight, pictures of the useless and ravenous, who is perhaps Chinese language or African, actors and dancers performing many elements to the wildest of music: disgraced Chinese language politicians, Rhodesian demagogues, African dancers. And thru all of it, pirouetting en pointe throughout the pages of a magnified atlas, is a black ballerina wearing a communist uniform, however waving a flag like Delacroix’s Liberty Main the Individuals. All of the beliefs – and disasters – of revolution come collectively on this pageant, its aesthetic a stupendous extension of Kentridge’s charcoal animations, the place the ghosts of the previous all the time hang-out the current.

Post a Comment