Even the Queen of England, mentioned Andy Warhol, can’t purchase a greater scorching canine than the bum on the sidewalk. One other factor the Queen of England couldn’t purchase was a flattering portrait by Lucian Freud. When he painted Elizabeth II initially of this millennium, he handled her face with the identical harsh objectivity as every other face, a closeup of wrinkles and sags, tight mouth and sad eyes, below coils of gray hair, with the absurd addition of a crown. Was Freud a republican? He actually wasn’t a sentimental royalist.

This royal head rests uneasy on a wall of equally unvarnished portraits of well-known and unfamous faces within the Nationwide Gallery’s addictive centenary blockbuster Freud present. It's a key to his artwork, for it's so movingly unpretentious – in an virtually adolescent method – in its declaration of the artist’s ethical mission. A portrait, says this portrait, should be brutally true. Head to head with a monarch, an artist has solely two choices: be a courtier or a truth-teller. Freud takes the trail he all the time does, warts and all. His genius is his harmless simplicity. Simply look and be sincere about what you see. It was the clearest, most humble of creeds, but it meant ignoring a truckload of philosophical and inventive distractions, over an extended working lifetime.

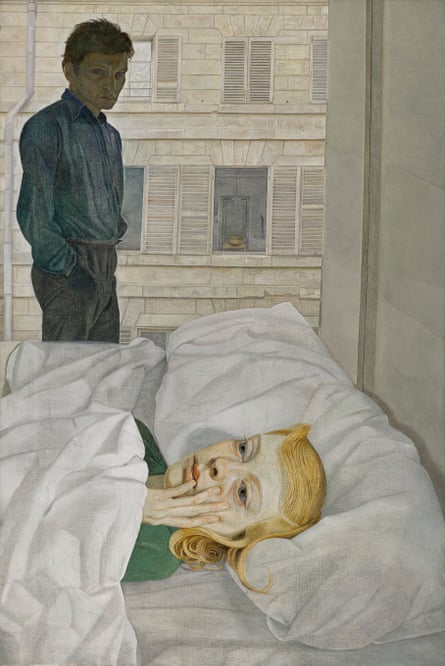

He’s clearly already electrically conscious of his vocation within the first self-portraits on this present, out of which he stares on the world with enormous eyes from a razor-sharp face. He flatters himself, certainly? But images affirm he actually was that handsome. In his 1954 portray Resort Bed room, he stands in shadow, arms in pockets, brooding below hedgehog hair, whereas his new spouse (he was on his second) Caroline Blackwood lies in mattress within the foreground, pale and brightly lit, her hair tangled on the pillow, her lengthy, skinny fingers pulling at her cheek in obvious misery. It was their honeymoon.

It’s a second of hysteria and thriller in a younger marriage, as we glance from her pallor to his shadowy ferocity to a window throughout the road via which we glimpse inside one other room, a theatre of various tales. Freud may be staging a fiction right here, besides it’s so gray and actual. Very early on, this present makes plain, Freud rejected something fanciful, surreal or mythological: as a younger man he knew Picasso however didn’t share his modernism. Or his pal Francis Bacon’s theatricality.

Blackwood later turned a Booker-shortlisted novelist. They arrive at you so vigorous on this present, the extraordinary characters of Freud’s world, from his first spouse Kitty Garman gazing abstractedly as she holds a kitten by its throat to Sue Tilley, whose magnificent mottled flesh fills your mind as you ponder her in one of many final grand canvases right here, Sleeping by the Lion Carpet.

Garman and Tilley are painted in completely completely different types, many years aside. One of many delights of seeing his artwork on the Nationwide Gallery is that, afterwards, you may have enjoyable recognizing his influences in its assortment. Within the 1947-48 canvas Woman with Roses, Freud paints Kitty as she painfully squeezes the thorny stem of a pink flower. You’ll discover her cousins in Hans Holbein’s equally medical Renaissance portraits.

Seeing Freud on this museum of European portray takes him out of a boringly British context. It frees his early work from parochial comparisons with prosaic homegrown artists of the Nineteen Forties and 50s and as an alternative makes you see his affinity with Holbein, Albrecht Dürer and Lucas Cranach the Elder. Born in Berlin in 1922, grandson of Sigmund Freud, dropped at Britain by his dad and mom within the 12 months Hitler turned chancellor – it’s no surprise Freud painted in his youth like a German Renaissance portraitist.

5 many years later, he was making an attempt to color like Titian. You'll be able to examine his nudes with Titian’s two masterpieces Diana and Actaeon and Diana and Callisto, in the primary assortment, which he campaigned to purchase for the nation. Titian’s two opulent shows of flesh pose our bodies in complicated interrelated teams – and Freud does the identical factor in his epic 1993 portray And the Bridegroom.

Two individuals are mendacity bare on a mattress on this colossal masterpiece. Nearest to us is Nicola Bateman, a tiny, skinny, pale determine. Is she actually that small or is it simply that she is dwarfed by her immense husband, queer efficiency artist Leigh Bowery? His tanned flesh spreads mountainously beside her. They’re resting collectively on a grey-covered mattress in Freud’s studio, whereas he patiently inspects their anatomies. He observes Bateman’s dimpled hips and her little foot resting on Bowery’s big thigh, whereas Bowery – a heroic exhibitionist even at relaxation – lets us see the purple snake of his penis. It’s properly in proportion with the remainder of him: a bratwurst, not a frankfurter.

It might be tempting to name this portray a butcher’s freak present, a chilly comparability of two strikingly completely different our bodies – apart from the deep tenderness that pervades it. That light element of Bateman’s foot ensuring Bowery’s nonetheless there as she slumbers, together with her curled-up, childlike sense of being protected, confirms it is a portray of affection. Nevertheless it was the large who was weak. Bowery would quickly die after contracting Aids. Listed below are two people defying all classes. Freud’s dedication to inform the reality will not be callous or chilly. It's, you may see right here, profoundly attentive to our selection and our unity.

Freud’s modifications of fashion don’t actually matter. His painterly means aren't as vital because the depth of his goal – to set one other earlier than him, in William Blake’s phrases. Greedy somebody’s very being is what he desires to do. Typically he appears extra like a sculptor than a painter: his individuals are so stable. Close to the Queen, his portrait of David Hockney is as meatily alive as if you happen to have been standing subsequent to the actual Hockney.

That is an ethic of artwork. Certainly it's a morality of life. And it certainly has one thing to do with the truth that Freud lived when he and his brothers may so simply – as he informed his biographer William Feaver – have “ended up in gasoline ovens”. Freud paints life within the face of demise. In his 1968 portray Buttercups, a jug stands in a sink, full of flowers. I’ve all the time puzzled why Freud’s portrayal of vegetation all the time appear so unhappy. Taking a look at this, it’s all of a sudden clear. He pays such meticulous consideration to every little yellow buttercup: this isn’t a portray of flowers normally, not even buttercups. It’s about these single particular buttercups – they usually’re dying.

Freud paints folks the identical method. His portrait of Bacon’s lover George Dyer is touching: Bacon painted Dyer in grandiose, tragic triptychs however Freud reveals him as merely a beaten-up bloke, somebody actual. And somebody who took his personal life.

Freud doesn’t flatter however neither does he despise. He's an artist for now, his lust for human physicality all-embracing. The Elizabethan age is over. The Freudian age lives on.

Post a Comment