In the 2023 spring budget, UK chancellor Jeremy Hunt unveiled a raft of measures designed to boost economic growth and productivity. To achieve this he has overhauled both pensions and childcare support, which will have implications for current and future personal finances.

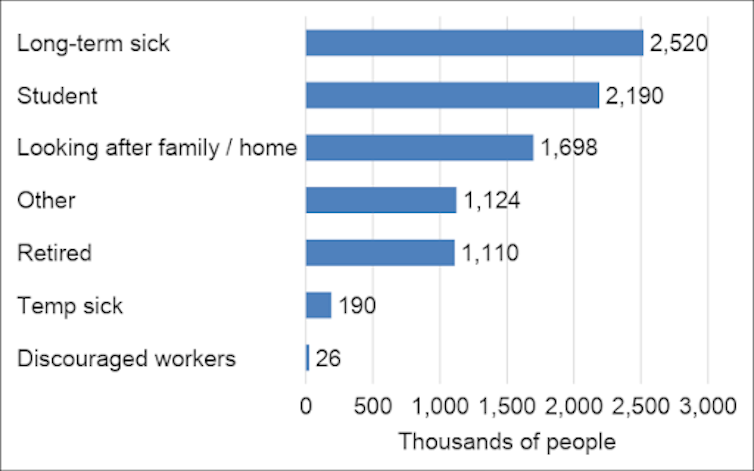

The Chancellor wants to encourage the UK’s 8.9 million “economically inactive” working age people back into the labour force. As the chart shows, this means focusing mainly on those who are retired, ill or caring for children.

Reasons for not working

Author provided based on data from the Office for National Statistics

Even if you aren’t in one of these groups, the new changes could affect your finances or working life in three key areas:

Tax-related retirement benefits

From April 6 2023, the overall annual limit on contributions for pension savings will rise to £60,000 from £40,000. The cap on the total pension saving a person can have over their lifetime, currently £1,073,100, will also be abolished. These changes target the particular problem of high earners, such as doctors quitting the labour market early to avoid a hefty clawback of pension tax reliefs when they exceed these caps if they work for longer and therefore the value of their pension savings keeps growing.

Pension tax reliefs typically benefit rich people the most. Back in January, it was estimated that income tax relief on pensions this year would total £51.7 billion. That’s a fifth of the £249.8 billion total income-tax revenue, and broadly speaking around half of that relief goes to the richest 15% of people.

Research suggests that pension tax reliefs do not increase the total level of saving, they merely cause savers to switch into pensions from forms of saving that aren’t subject to tax relief. This calls into question the rationale for spending such large sums of taxpayer money on subsidising the savings of wealthy people who would most likely set aside enough for retirement anyway.

Instead, it is time for a wholesale redesign of the pension tax system to target support where it is genuinely needed. For example, topping up the pensions of people (mostly women) engaged in unpaid caring work -– and in the process a simpler, more targeted system without the need for complicated annual caps could remove the side-effect of high earners retiring early.

A more widely useful pension-tax change helps anyone who chooses to “flexibly” access pensions savings, for example, by drawing out money from age 55 onwards – maybe to cope with an emergency or the current cost of living crisis. While you might intend to rebuild your retirement savings later, there will be a limit on how much you can continue to save tax free. From April, this limit will be £10,000 per year, under the latest budget, up from £4,000 annually at the moment.

Reduced childcare costs

Targeting the 1.7 million economically inactive who are engaged in unpaid care work at home, the budget includes a phased extension of the 30-hours-a-week free childcare scheme for children aged one and two in working families. The government seems to have paid heed to advice to address the woeful underfunding of free childcare places and has said it will increase this - for example, by an average of 30% at the two-year-old rate- which will hopefully prevent the closure of more nurseries.

Working parents on universal credit can currently claim back 85% of childcare costs up to a limit of £646.35 per month for one child and £1,108.04 for two or more children. In a welcome move, the budget will enable the costs to be claimed in advance rather than arrears. This removes the barrier of needing to find a substantial sum to cover childcare payments up-front before being able to start a job.

The upper limits are also being increased to £951 a month for one child and £1,630 for two or more. However, this will have only a limited impact since few families claim anything near the maximum amount.

Ground Picture/Shutterstock

Help for those with long-term health conditions

The recent budget included a white paper setting out carrots and sticks to get people with long-term health conditions back into work.

The paper outlines a plan for more employment support for people with disabilities and health conditions. This includes nationwide “work coach” support provided via Jobcentres, an extension to the Work and Health Programme, which helps people find jobs if they are in certain categories such as refugees, care leavers, homeless, ex-armed forces reserves or are living with disabilities. A new “in-work progression offer” is designed to persuade people in work on universal credit, including people with disabilities, to increase their earnings and move into better-paid roles.

The government also seems to be setting great store in the opportunities opened up by the growing trend towards hybrid and home working. But health and disability charities are concerned that these measures could be used to force people into unsuitable jobs.

Overall, these measures clearly aim to retain people in work or entice them back. But the government should remember that ill health can make it very hard or impossible to commit to regular work. And many of those who are caring for their children or others or who have already retired may be doing so by choice rather than because they see barriers in the way of working.

Post a Comment