Jimmy Akingbola says he can now sympathize with why his mother gave him to child services when he was 2 years old.

"My mom left me," he recalls to TODAY.com. "But actually, if you break it down, it comes from a place of protection."

Akingbola says his mom, Eunice, lived with schizophrenia and was no longer able to take care of him, but she didn't want him to go without certain necessities in life.

"She was on medication (and) she was trying to get better," he says. "I was supposed to go back to my mom, but the illness just kept fluctuating and got worse. So the decision was to allow me to be fostered."

His personal experience in the foster care system helped to inspire some of his “Bel-Air” character Geoffrey's storyline — specifically the part about Geoffrey's son who was adopted by another family and later comes back into his life — an aspect that Akingbola wanted included.

Now, the “Bel-Air” star is sharing his journey through the foster care system in London for the first time in his documentary, “Handle With Care,” which is currently streaming on Peacock.

In an interview with TODAY.com, Akingbola opens up about his parents' arguments that led to him being fostered, how he learned to forgive them and why he's now proud to have went through the foster care system.

'An excuse to break away'

How Akingbola ended up in foster care is more layered than just his mother's mental health journey.

He and his three biological siblings originally lived with their parents. At the time, his father, Akeen, was unaware of his mother's mental health diagnosis and how she would travel to help cope, Akingbola says. Her travel prompted his dad to question his paternity.

"There was times that my mom spent away ... from him — (and) went to Nigeria," he says. "Around that time was the time that I arrived. For him, I think he wanted to get out. I feel like he used my birth and the question mark on it as an excuse to break away."

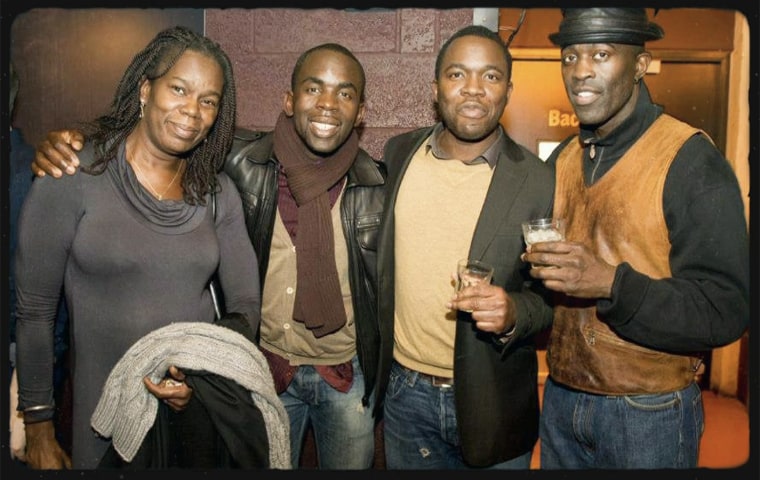

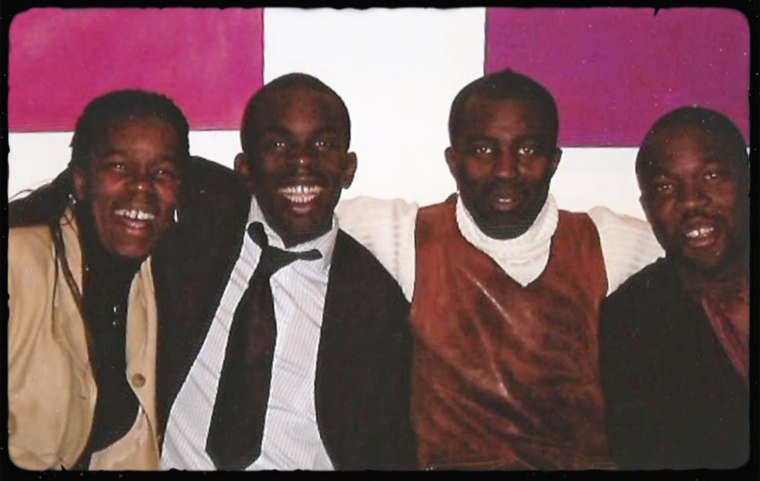

His father disowned him, divorced his mother and kicked them both out while keeping the other three children. His mother later dropped Akingbola off at child services. He was then placed with the Crowe family, whom he lived with until he was 16.

"I can never blame my mom," he says. "Even being abandoned at the social services office, I remember when I first got told that (at age 7). I was in tears, and yet, I still couldn't find the anger for it because I knew that wasn't her. That was her struggling with something financial, but also her mental state not being in a best place."

He says he's asked his mother about his father's claims and her response was: "Don't listen to him. You are his son."

Akingbola says his mother visited his foster home every two weeks. His siblings also regularly visited, and so did his dad, eventually.

Akingbola and his father reconciled when he was a teenager to the point that he finally "felt accepted" and they "really got close," he tells TODAY.com.

But on a later visit to Nigeria, his dad said, "I've been a father figure to you, but I'm not your father," Akingbola recalled in the documentary.

"OK, dad," Akingbola responded. "Let's do the test."

But after his father agreed to a DNA test, Akingbola says his father never returned his calls to confirm it.

"As a Nigerian man, if he broke up his family (because) he believed something had happened and then the blood test says that he's wrong?" Akingbola says. "He's (from) a certain generation. He can never be wrong. So rather than do it, he just refused to. That's what I believe."

Even so, Akingbola extends empathy to his father.

"There's something in me that goes, OK: You're heartbroken, you have three sisters, you're the eldest, you lost your dad young, you moved to London with a young family, you were struggling, you're a Black family in a white country and then your wife's got schizophrenia," he says. "I have to give him grace.'"

'A Black son or brother'

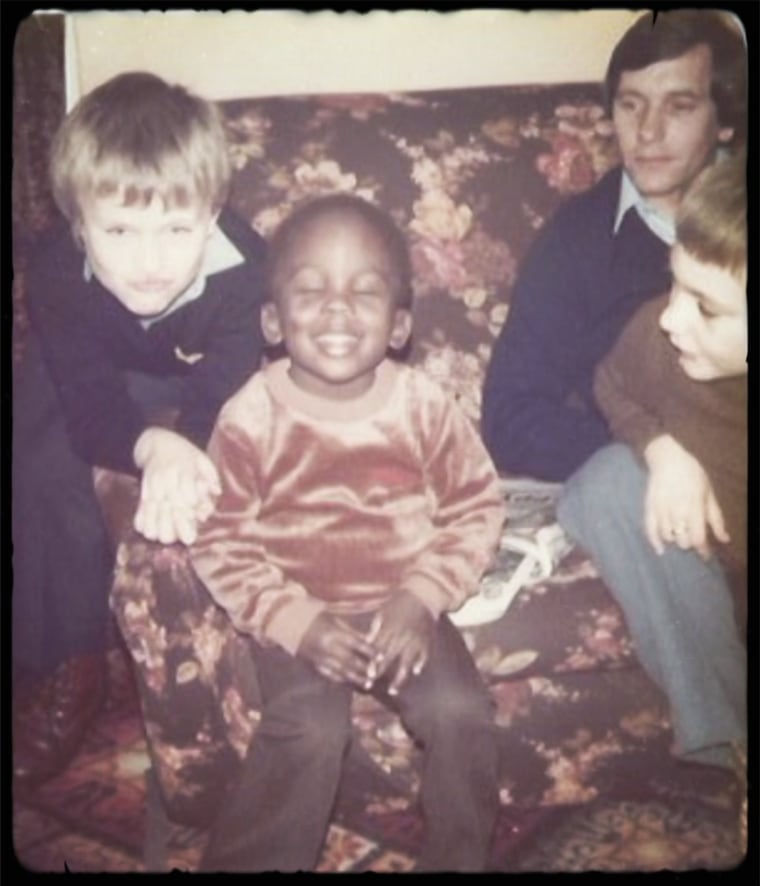

Akingbola lived with one family, the Crowes, until he was 16 years old. The Crowes are a white family, and Akingbola says they are loving, accepting and feel like family.

But as a kid, he felt othered as the only Black person in the house, in the neighborhood and in the school he attended.

Still, Akingbola credits his positive foster care experience to the Crowes' loving and understanding of Black culture before they got him.

“They would be called a woke family,” Akingbola says, noting that his foster mother listened to reggae music while his foster brothers listened to Luther Vandross and rappers NWA, Run DMC and the Fresh Prince, also known as Will Smith who later starred in "The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air," the series that “Bel-Air” is based on.

“It wasn’t just because they bad a Black son or brother,” he says. “Those things were in their lives anyway.”

Sleepovers with friends also helped Akingbola connect with his identity, as did spending time at Community Links, a youth house with programming for kids. The house has since been renamed in honor of Akingbola, who supports cultural awareness when parenting.

“It’s a fine line because you’re showing the kid that they’re different, but there’s a way of showing that you’re different and showing it with love and education and elevation,” he says.

He says he grappled with how to love his foster family while still holding so much love for his biological family.

"I am here because of both families, so I can’t dismiss anybody," he says. "I used to yearn to be with my biological family. I remember in my teens to early 20s, I got to the point where, if I’m yearning for that, what does this look like, this loving foster family, my family (with) unconditional love that's been there for me?"

"It’s like I’m dismissing that and then when I looked at it, I’ve got this great hybrid of two families that know each other, that love me that got along and loved each other as well," he continues. "And that’s perfect. It didn’t need to be one or the other."

The two families have blended together seamlessly while also establishing some boundaries. For example, Akingbola says the Crowes never adopted him because his mother was still in his life. They hoped she'd one day get better and be able to take him back.

Akingbola's mother died during the pandemic, as did his biological and foster fathers and one of his biological brothers.

In the documentary, his two remaining biological siblings say Akingbola "had it better" because he grew up with a "loving family" in a "safe space," because their space at home "was dangerous."

"That was the first time I heard that from my my older siblings," he says. "It was hard to hear. It made me realize I had a vision of how the family was from the foster home, but they were going through something. It was a really tough time. Their environment wasn’t as loving as mine or as safe as mine.... Hearing them say that I just realized, in the middle of making the doc, they had their journey as well."

'Healed'

These days, Akingbola says he's on a journey toward peace.

"Where I am now, I feel like I'm in a healed place," he says.

He likens his current goal as opening and looking "at the bottom drawer."

"We've all got some drawers in our lives, and it's a bottom drawer that I never really opened because there was a lot of sadness and pain," he says. "There's abandonment, there's mental health with my mom, there's a divorce of the family, there's identity."

Akingbola says while he previously buried this part of his personal story, it was always present in his acting.

"I worked through my trauma through my roles," he says. "I think each role I had, there was something in it that I could connect to, and it was my version of opening a drawer. But an added safety net because it's a character."

That personal connection can be seen in his "Bel-Air" character Geoffrey's storyline about the adoption of his biological son by another family — a storyline that Akingbola says was already under consideration, but officially added after showrunners caught wind of his documentary.

"We had a conversation and I just gave them everything that I've been through," he says. "Then they wrote the brilliant episode that we did."

That was just a bonus, though. The real triumph, he says, was getting real with himself and not running from his trauma.

Post a Comment