Fresh proof that the Nazis set up fake auctions and phoney paperwork to disguise their looting of art and valuable possessions has been uncovered by an amateur sleuth researching her own family mystery.

French writer Pauline Baer de Perignon’s investigation has revealed the fate of a missing collection of art that included work by Monet, Renoir and Degas and also exposed the reluctance of Europe’s leading museums to accept evidence of the deceit.

Baer was prompted to look into the past when she bumped into an English cousin who told her he believed the family had been “robbed”.

“The whole thing has changed my life,” said Baer this weekend. “I have had to look back at a long-forgotten family story as well as at the hidden secrets of the Gestapo. And then I had to confront the truth about paintings held by galleries such as the Louvre and the state museum in Dresden. I was so naive when I started.”

Baer’s three years of research have led not just to a better understanding of the way in which significant works of art were systematically stolen after Germany invaded France, but will culminate later this month in the high-profile sale of a recovered painting at Sotheby’s in New York.

Portrait of a Lady as Pomona, by the revered 18th-century French artist Nicolas de Largillière, once belonged to her great-grandfather, the Parisian collector Jules Strauss, and was only returned to his descendants last year. It is now expected to sell for $1m-$1.5m (£750,000-£1.1m). “I could have asked my father to tell me about Jules Strauss, but I never did,” Baer has explained. “My father died when I was 20, before I was bold enough to ask him about the war, about his parents and grandparents, about his emotions and his memories.”

Baer’s curiosity was aroused when she bumped into her cousin Andrew Strauss at a concert in Paris eight years ago. The two had not met since she was a teenager, but he told her that he worked at Sotheby’s and believed the apparent sale of the Strauss collection in the early 1940s was “shady”. He mentioned the involvement of dummy companies, Nazi officers and museum inventories to his bemused cousin. “Andrew’s words sent my mind tumbling down a rabbit hole,” said Baer.

Armed with a scribbled note listing the names of famous artists, Baer began to piece together the lost past. She was now as interested in finding out what happened to her distant family members as in the fate of the missing art. A book about her efforts, The Vanished Collection, has already made waves in France, where it was published last year and where critics have compared it to a compelling suspense novel. A reviewer for Elle said it was as “devourable as a thriller”, while others have compared the family’s story to those of other famous Jewish families whose art was looted in the war, such as the Camondos, the Rothschilds and the Ephrussis.

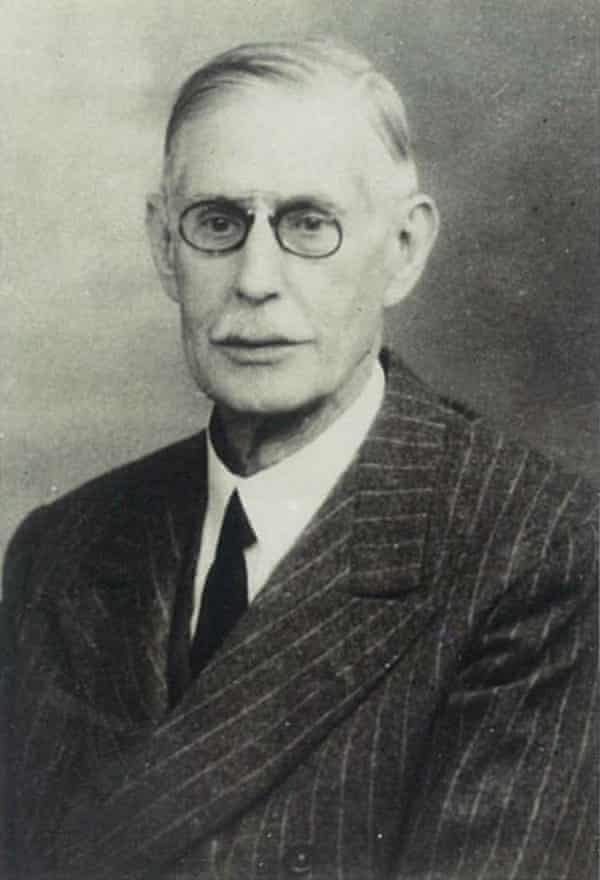

At the start of Baer’s inquiries, all she had was one photograph of Strauss, her illustrious great-grandfather, and another of the many portraits hanging on the walls of his former home on Avenue Foch in Paris. She knew the apartment had gone, but that there was one elderly living relative with first-hand knowledge of what had happened.

She delved into the archives of great museums and asked difficult questions of the French ministry of culture. She was surprised to discover how the thefts had been covered up, but her English translator, Natasha Lehrer, believes the most powerful part of the book concerns howmodern art institutions have dragged their feet and, at worst, avoided doubts about the ownership of important paintings.

“What Pauline stumbled upon was an apparent unwillingness among those leading various large state museums to admit that they were holding looted works of art until very recently,” said Lehrer. “This despite the fact that families and collectors often had all the provenance information available to identify them as the rightful owners. There has been a notable reluctance to return artworks.” The English version of Baer’s book is to be published next month by Head of Zeus.

Baer tracked down the portrait by Largillière to Dresden’s state art collections and found archival evidence to prove that Strauss had been forced to sell it. The masterpiece had apparently been acquired in 1941 for the Reichsbank in Berlin and then transferred to the ministry of finance, before going to Dresden in 1959. Baer found the words “Collection Jules Strauss” next to the Largillière’s listing in the German Lost Art Foundation, but was then told that the Dresden museum’s director was not minded to return it. She was questioned about whether Strauss was originally happy to sell, despite evidence of laws that prevented Jews from profiting by such deals.

“The more I continued with my investigation, the more I realised how unlikely it was that Jules had been able to avoid his collection becoming seized by the Nazis,” said Baer. “Even before the invasion of France, the Germans had compiled a list of large French collections.”

Dresden’s state art collections has since said: “The investigation of this complex case was as extensive and thorough as is necessary to ensure that a work of art is returned to its rightful owner.” The portrait’s sale in New York this month will now allow all 20 of Strauss’s heirs a share in its value.

Painted between 1710 and 1714, when Largillière was at the height of his powers, the sitter for the portrait is thought to be Marie Madeleine de La Vieuville, the Marquise de Parabère, mistress of Philippe II, Duc d’Orléans. She is depicted as Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruit and abundance.

Strauss, a Frankfurt-born banker, built an extraordinary collection of art, ranging from antiques to the Impressionists, while he was in Paris. It is now clear that much of it was then stolen or forcibly sold by the Nazis.

Post a Comment