Whether it’s due to the unsure instances by which we stay, the dismal nature of our political leaders, or the rise of rightwing populism, we now have had a spate of books in recent times on management in fashionable historical past. From Frank Dikötter’s Find out how to Be a Dictator to Henry Kissinger’sManagement, the format appears to be to string collectively chapters on numerous world leaders who modified the course of historical past, for good or unhealthy, and replicate on the patterns between them.

The most recent providing is Ian Kershaw’s Character and Energy, by which the good historian of Hitler and his motion pens a dozen lucid portraits of the leaders – half of them dictators, the others democrats, to various levels – who formed Europe’s twentieth century.

His start line is Karl Marx’s dictum of 1852: “Males make their very own historical past, however not as they please, in circumstances of their very own selecting, however quite underneath these immediately encountered, given and inherited.” How far is the chief’s energy formed by character, and the way a lot by circumstance, Kershaw asks. Every chapter follows the identical sequence of subsidiary points from the preconditions of the chief’s rise to a short dialogue of his legacy.

Kershaw additionally attracts from Max Weber’s principle of “charismatic” management: the charisma of the chief is created by his following of believers, whose beliefs are invested within the “chosen one”, or manufactured for him by his motion or the state by way of a character cult. Kershaw was a pioneer of this strategy. One in every of his greatest early works, The Hitler Delusion (1987), confirmed how Hitler’s energy rested on his propaganda picture and its public notion.

He emphasises how extraordinary leaders are created by crises. This goes for the dictators who got here to energy by way of social revolution (Lenin), the collapse of parliamentary politics (Mussolini) or financial despair (Hitler), and leaders in democracies whose greatness got here as saviours of their nation in a time of battle (Churchill and De Gaulle), or for individuals who steered their nation to democracy after ruinous dictatorships (Adenauer, Gorbachev).

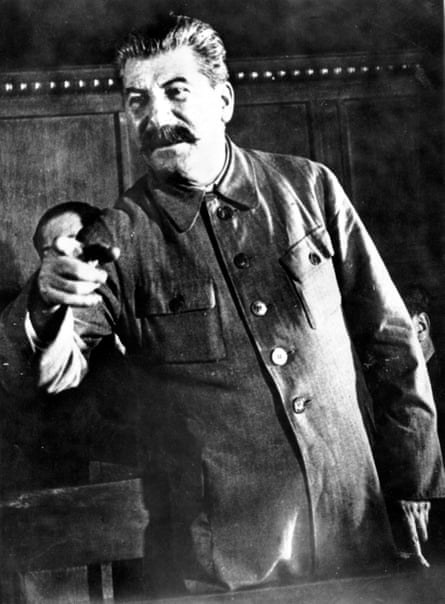

Crises may be fabricated too, a degree Kershaw might need made extra of. It was the “battle scare” of 1927 (when Pravda revealed pretend information of a British deliberate invasion of the USSR) that enabled Stalin to defeat his rivals for the management and power by way of his model of the five-year plan; and whipped-up fears of Bolshevism that allowed Mussolini and Franco to rally frightened Catholics behind their trigger.

Kershaw fills his energetic profiles with revealing particulars of the leaders’ characters, their working type and relations with the ruling constructions that supported them. Margaret Thatcher “thrived on abrasive argument and combative dispute”, counting on her “workaholic habits” and ‘“forensic interrogative powers” as a educated lawyer to “carry her case in opposition to cupboard colleagues who had been much less nicely ready or extra submissive of their character”. Franco wore down the resistance of his ministers by not permitting bathroom breaks in conferences that might final all day and evening. His bladder management was “extraordinary”, Kershaw informs us.

He additionally highlights the errors that leaders made to result in their fall, analysing how far these may be defined by their very own cussed personalities, ideological blinkers, or by the hubris that impacts so many leaders, particularly dictators, after they’ve been in energy for too lengthy. Such errors are obvious solely in hindsight. Putin’s resolution to invade Ukraine will go down in Russia’s historical past as a mistake if it ends in a defeat, however “victory” will erase the army blunders and atrocities from the nationwide reminiscence. Energy decides the whole lot.

As you'll anticipate, Kershaw is at his most masterful in his sketches of the three German leaders on this guide. He's additionally excellent on Mussolini and De Gaulle. He's much less convincing on Lenin and Stalin, the place his reliance on secondary sources makes for a flat and standard account. He doesn’t actually perceive the sacred base of charismatic energy in Russia, the Byzantine custom of saintly tsars and princes that transmogrified into the cults of Lenin and Stalin; nor the patrimonial nature of autocracy in Russia, the place the chief is the grasp of the land and its individuals, a type of despotism and enslavement of society that goes from the Mongols to Stalin (“Genghis Khan with a phone”, because the Bolshevik Bukharin described him). The very phrase for energy in Russian (vlast) comes not from motion, as in western languages (puissance, potenza, macht, and so on), however from the time period for a fiefdom, a territory owned by its ruler.

Kershaw devotes the ultimate chapter to a summing up of the elements that outlined the train of energy by all 12 leaders within the guide. His function, as he tells at first, is to check seven propositions about private management. They're all pretty apparent. Did we actually have to learn this guide to study, for instance, that “single-minded pursuit of simply definable objectives and ideological inflexibility mixed with tactical acumen allow a particular particular person to face out and acquire a following”? Or that “focus of energy enhances the potential affect of the person – typically with unfavourable, typically catastrophic penalties”?

Maybe in the long run the cultural specificities of the seven international locations explored on this guide, their differing traditions of understanding energy and authority, don't lend themselves so simply to basic ideas. Is it even significant to check the modes of management in methods as numerous because the Third Reich and Tito’s Yugoslavia or Britain underneath Churchill and Thatcher? There may be a lot to be admired in Kershaw’s cogent and astute evaluation of those leaders in energy, however I’m undecided there are any basic classes to be realized.

Orlando Figes is the writer of The Story of Russia (Bloomsbury)

Post a Comment